Chapter 9: File Systems

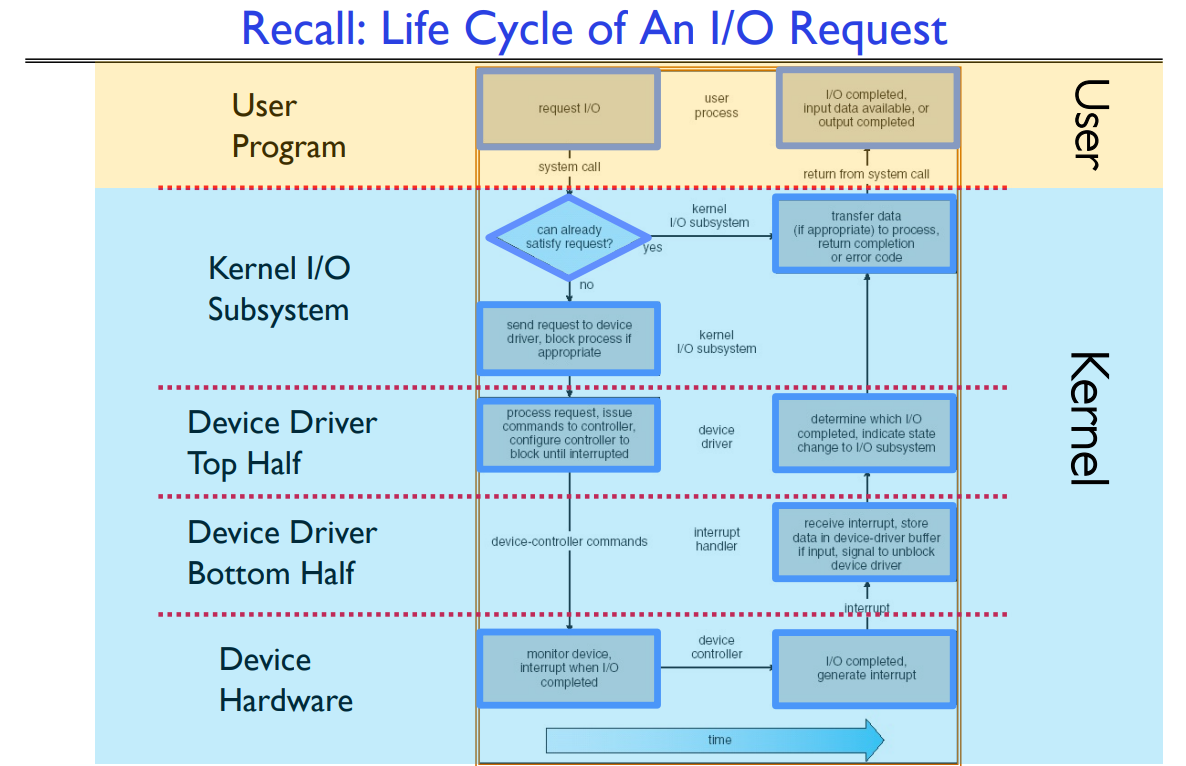

I/O #

Drivers #

A computer handles I/O on its end using several mechanisms:

- The bus, a common set of communication wires, carries data transfer transactions between devices.

- A typical modern bus standard is PCI (Peripheral Component Interconnect), which is a parallel bus that can handle one transaction at a time. One major downside to this is that the bus speed must be set to the slowest connected device.

- PCI has evolved into PCI-Express, which is a collection of fast serial channels (lanes) in which devices can use as many as necessary to achieve a desired bandwidth. In this ways, devices can still use the old PCI standard, but don’t have to share lanes with other devices.

- Controllers, which sit between the CPU and I/O devices and contain a set of registers and memory that can be interfaced with.

A processor can interact with device data in one of two ways:

- Port-Mapped I/O: using assembly instructions to directly grab data.

- Memory-Mapped I/O: devices asynchronously read and write data from memory, and the CPU can use standard load and store operations to access this memory. Memory-mapped IO generally requires polling (see below for consequences of this fact).

Transferring data to and from a device controller can be done in one of two ways:

- Programmed I/O: every byte is simply transferred via port-mapped or memory-mapped I/O operations.

- This is good because it keeps the hardware and software simple, but the amount of processor cycles it requires grows proportionally to the amount of data. (i.e. bad for huge chunks of data)

- Direct Memory Access (DMA): give the device controller direct access to a memory bus (acts on physical memory).

- The top half of a DMA scheme, the device driver interface, starts a request.

- The bottom half consists of the code that executes on DMA completion (when the DMA controller interrupts the CPU).

There are two ways to notify the OS about I/O events:

Polling is when the OS periodically checks device status registers for operations that need to be completed.

- This is best for frequent, predictable I/O events, since there is low overhead; however, polling can waste CPU cycles if no I/O events are occurring.

Interrupts are generated by the device whenever it needs service.

This is best for handling infrequent or unpredictable events, since there is high overhead on interrupt.

Modern devices usually combine polling and interrupts: for example, network adapters could use interrupts to wait for the first packet, then poll for subsequent packets.

Several types of standard interfaces can be implemented to make accessing devices more consistent:

- Block devices access blocks of data at one time using

open(),read(),write(), andseek().- This type of interface is best used for storage devices such as hard drives or CD readers.

- Character devices access individual bytes at a time using

get()andput().- This type of interface is most appropriate for devices that use small amounts of data, such as keyboards or printers.

- Blocking interfaces put the process to sleep until the device or data is ready for I/O.

- Non-blocking interfaces return quickly from read or write requests with the number of bytes successfully transferred. These interfaces are not guaranteed to return anything at all.

- Asynchronous interfaces return pointers to buffers that will eventually be filled with data, then notifies the user when the pointer has been obtained.

Storage Devices #

HDD #

Hard drives are magnetic disks that contain tracks of data around a cylinder.

HDD’s are generally good for sequential reading, but bad for random reads.

Disk Latency = Queueing Time + Controller Time + Seek Time + Rotation Time + Transfer Time

- Queuing Time: amount of time it takes for the job to be taken off the OS queue

- Controller Time: amount of time it takes for information to be sent to disk controller

- Seek Time: amount of time it takes for the arm to position itself over the correct track

- Rotation Time (rotational latency): amount of time it takes for the arm to rotate under the head (average is 1/2 a rotation)

- Transfer Time: time it takes to transfer the required sectors from disk to memory

HDD Question: Calculating size and throughput

Suppose a hard drive has the following spects:

- 4kb sectors

- 3 million sectors per track

- 100 tracks per platter

- 2 platters (1 sided)

- 5400 rpm

- 5.6ms average seek time

- 1ms controller+queue time

- 140 MB/s transfer rate

The size of the hard drive is equal to (size of sector) x (num sectors per track) x (num tracks per plattter) * (num platters) = 4096B * 3000000 * 100 * 2, or about 2.46TB.

For a 64KB read, the throughput can be calculated as bytes/latency, or

64KB/((queue + controller time) + seek time + rotation time + transfer time).

- The queue, controller, and seek times are all given in the problem.

- Average rotation time is (1/2) * (time for one rotation) = 0.5/5400 = 5.55ms.

- The transfer time is (bytes)/(transfer rate) = 64/140 = 0.457ms.

- All together, the throughput is 64KB/(1+ 5.6 + 5.55 + 0.457)ms = 5079KB/s.

SSD #

Solid state drives store data in non-volatile, NAND flash memory cells that don’t have any moving parts.

- This means that seek time and rotation time are essentially reduced to a single short access time.

- Writing data to an SSD can get complex and time-consuming, because writing can only be done to an empty page. Generally, writing takes 10x as long as reading, and erasing blocks takes 10x as long as writing.

- To mitigate long erasure times and lower NAND durability:

- Maintain a flash translation layer (FTL) which maps virtual block numbers to physical page numbers in RAM. This way, the SSD can relocate data at will without the OS caring.

- Copy on write: instead of overwriting the entire page when the OS updates its data, we can write a new version in a free page and update the FTL mapping to point to the new location. This allows writing without the costly erasure step.

SSD Latency = Queueing Time + Controller Time + Transfer Time

Queuing Theory #

Latency (response time) is the amount of time needed to perform an operation.

Bandwidth (throughput) is the rate at which operations are performed.

Overhead (startup) is the time taken to initiate an operation.

Latency for an n-byte operation = Overhead + n/Bandwidth (linear with respect to the number of bytes)

A server that processes $N$ jobs per second is better than $N$ servers that process 1 job per second due to load balancing decreasing utilization.

$\mu$ = average service rate (in jobs per second)

$S$ = $T_s$ = $m$ = average service time = $\frac{1}{\mu}$

$C$ = squared coefficient of variance = $\frac{\sigma^2}{S^2}$

$\lambda$ = average arrival rate (in jobs per second)

$U$ = utilization (fraction from 0 to 1) = $\frac{\lambda}{\mu} = \lambda S$

$T_q$ = average queueing time (waiting time)

$Q$ = $L_q$ average length of queue = $\lambda T_q$ (Little’s Law)

Memoryless service time distribution with $C = 1$ (M/M/1 Queue): $T_q = S \times \frac{u}{1-u}$

General service time distribution (M/G/1 Queue): $T_q = S \times \frac{1+C}{2} \times \frac{u}{1-u}$

Queuing Theory Questions #

A job enters every 5 seconds, and completes in 60 seconds. What is the average queue length?

- $L_q = \lambda T_q$ (Little’s Law).

- The average arrival rate, $\lambda$, is 1 job per 5 seconds, or 0.2.

- $T_q$ is 60 seconds.

- So $L_q = 0.2 \times 60 = 12$.

To solve for $\lambda$:

File Systems #

Best to worst ranked

Sequential Access:

- Extent-based (NTFS) - files are contiguously allocated

- Linked (FAT) - traversing linked list

- Indexed (FFS) - nested inodes

Random Access:

- Extent-based

- Indexed

- Linked

Disk Capacity:

- Linked

- Indexed

- Extent-based (prone to external fragmentation)

FAT #

FAT stands for File Allocation Table. This file system consists of a table with entries that correspond one-to-one with blocks and stores information in a linked list format. (For example, file number 31 could point to 62, which could point to 53… all of these blocks in the table when read in order create a file.)

- FAT is good for sequential access (due to linked list structure), but terrible for random access (since you have to traverse the list to get to where you want).

- FAT is not prone to external fragmentation since subsequent blocks can go wherever there is free space, but internal fragmentation is severe in small files since blocks are a fixed size and you need at least one for each file regardless of the size.

- FAT has poor locality for files and metadata since file information is not stored sequentially.

Linux FFS #

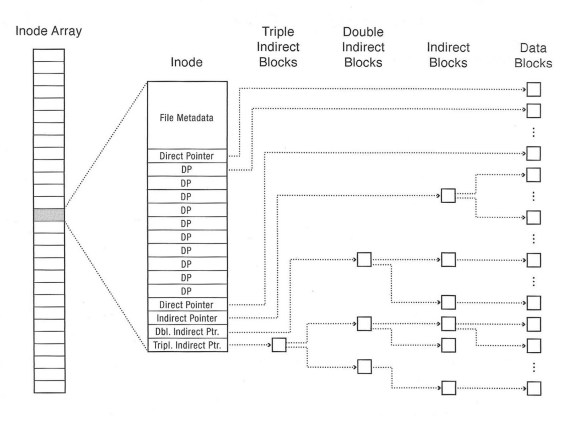

FFS (Fast File System) was used in early Linux systems and stores file information in inodes.

Each inode has file metadata and a list of pointers (direct, indirect, doubly indirect…) to blocks.

FFS can be optimized for HDDs by splitting up the disk into block groups. All files in the same directory should be placed in the same block group.

FFS is pretty good for sequential access if optimized, since inode information is all stored together, and blocks should have some amount of locality if they are in the same block group.

Random access is also pretty good because you can just pick the pointer that you want from the inode.

There is no external fragmentation due tot the inode structure, but internal fragmentation can be pretty severe due to the overhead and fixed size of inodes.

Hard link vs soft link

Direct pointer, indirect pointer, doubly indirect pointer

Inode

Calculate maximum filesize

NTFS #

NTFS (New Technology File System) is currently used by Windows. Rather than an inode array like FFS, it uses a Master File Table. Each entry in the MFT contains file metadata and data; the main difference is that MFT entries can have variable size.

- If a file grows too large, then extents add extra pointers into a MFT entry.

Directories #

In the three file system designs above, directories are represented as a file containing name-to-filenumber mappings where one entry in the directory corresponds to a file or subdirectory. (In FAT, file metadata is also stored in the directory.)

Name-to-filenumber pairs stored in directories are called hard links, which can be created using the link() syscall.

- In non-FAT filesystems, a file can have more than one hard link (i.e. be part of two different directories).

- A file will not be removed unless all hard links to that file are removed (so a reference count is needed to track them).

Soft links are a special entry in directory files with name-to-path mappings. Whenever the original name is accessed, the OS will look up the file corresponding to the stored path.

- Soft links can be created using the

symlink()syscall. - There is no reference count needed for soft links: if the path doesn’t exist or the file is deleted, then lookup will simply fail.

Distributed Systems #

Durability #

How do we prevent loss of data due to disk failure?

RAID #

Redundant Array of Inexpensive Disks. Rather than using one large, expensive, reliable disk, we use a large amount of small, expensive, unreliable disks and duplicate the data across the disks.

- RAID 0: No redundancy, striped volumes only. Very unreliable (any one disk failure means data loss).

- RAID 1: Disk mirroring. Every disk is fully duplicated onto its mirror. This produces a very large data availability and optimized read rates, but at the cost of needing 100% overhead.

- RAID 3: Parity disk. For every 3 disks, 1 additional disk is used to store parity information (so 1/4 of the data cost as RAID 1). If any one of the four disks fails, the data will still be intact.

- RAID 4: Disk sectors. Rather than operating at the bit level (like RAID 3), RAID 4 operates on a stripe level. Reads and writes must be done both to the original disk and the parity disk. This works well for small reads, but small writes can be problematic because every modified stripe needs to be parity checked. So the bottleneck becomes the parity disk.

- RAID 5: Interleaved parity. In a larger array, an independent set of parity disks each contain a few stripes for each drive. This cuts down on write bottlenecks since the chance of multiple drives writing to the same parity drive is reduced.

- RAID 6: RAID 5 with two parity blocks per stripe. So the drive array can tolerate 2 disk failures rather than just 1, at the cost of needing additional capacity.

Reliability #

Reliability is the guarantee that data remains in a consistent state after recovering from disk failure. This differs from durability since the former deals with the recovery step itself.

Transactions #

A Transaction is an atomic sequence that takes a system from one consistent state to another. Transactions follow four properties (ACID):

- Atomicity: transaction must complete in its entirety, or not at all

- Consistency: transactions go from one consistent state to another, and cannot compromise integrity

- Isolation: transactions should not interfere with each other if executed concurrently

- Durability: once a transaction is made, it will not be erased on disk failure.

Journaling Filesystem #

One way to guarantee reliability in a filesystem is to write operations to a log first. Once the whole transaction is written to the log, the disk will then apply the necessary changes.

- If the system crashes when writing to the log, then the transaction will not be applied.

- If the system crashes when applying disk changes, then we can simply observe that the log was not completed and re-apply the transaction. This is guaranteed to work for idempotent transactions (applying multiple times will have same effect as applying once).

EXT3 is basically FFS but with logging.

A log structured file system takes logging to another level by making the entire filesystem one log.

Consensus Making #

Previously, we talked about transactions on a single machine. But what if we have lots of computers, and need to coordinate transactions between them? It’s possible for one machine to be in an inconsistent state while the others are operating normally.

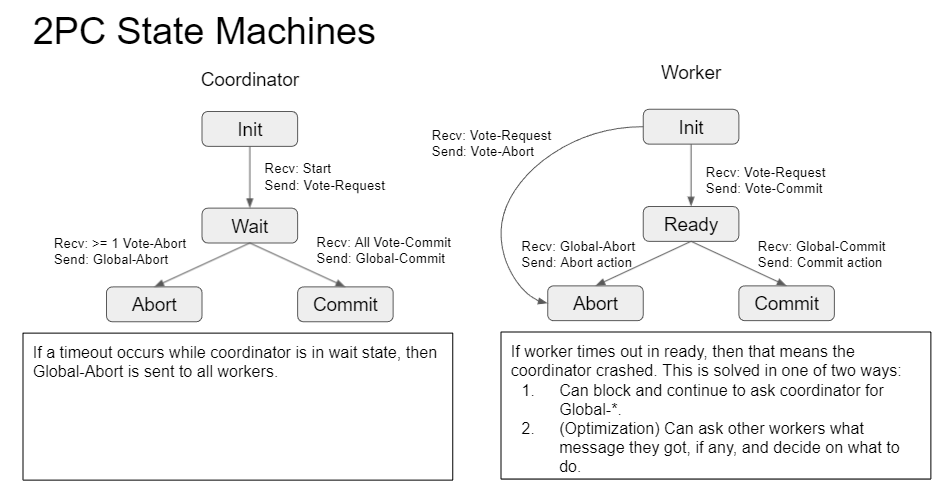

Two-Phase Commit #

2PC is a scheme for distributed consensus making. It proceeds as follows:

- One machine is the coordinator; all others are participants (workers).

- When the coordinator receives a request, it logs it then sends a

VOTE-REQUESTto workers. - Each worker records their own vote in their log.

- Each worker then sends a

VOTE-ABORTorVOTE-COMMIT. - If all workers send

VOTE-COMMIT, then the coordinator writes a commit in their log and sendsGLOBAL-COMMITto all workers. - Workers then perform the commit and send an

ACKon completion.

If one or more workers send VOTE-ABORT or times out, then the coordinator sends a GLOBAL-ABORT and no operation should be completed.

General’s Paradox:

Messages over an unreliable network cannot guarantee entities to do something simultaneously. However, this doesn’t apply to 2PC because there is no simultaneous operation.

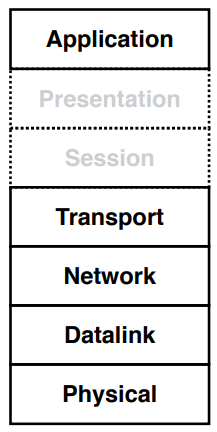

Network Systems #

Layers #

TCP vs UDP #

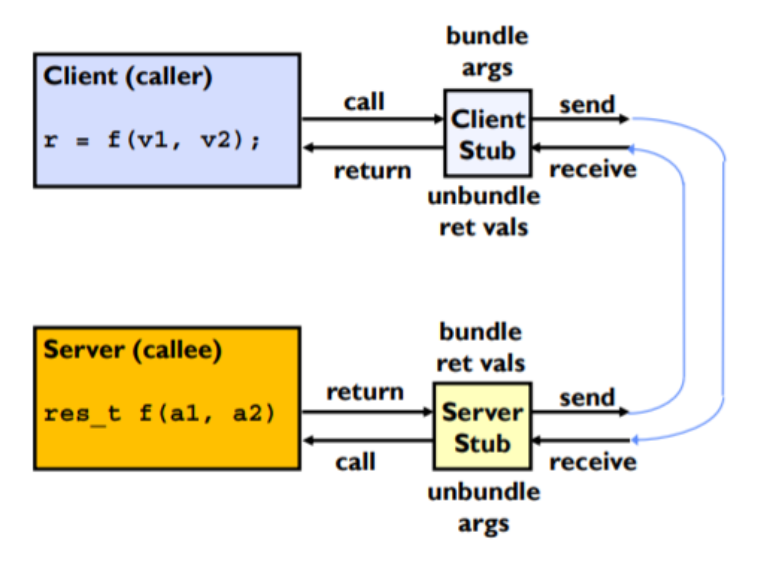

Remote Procedure Calls #

RPC’s (remote procedure calls) are an interface to call functions on another machine.

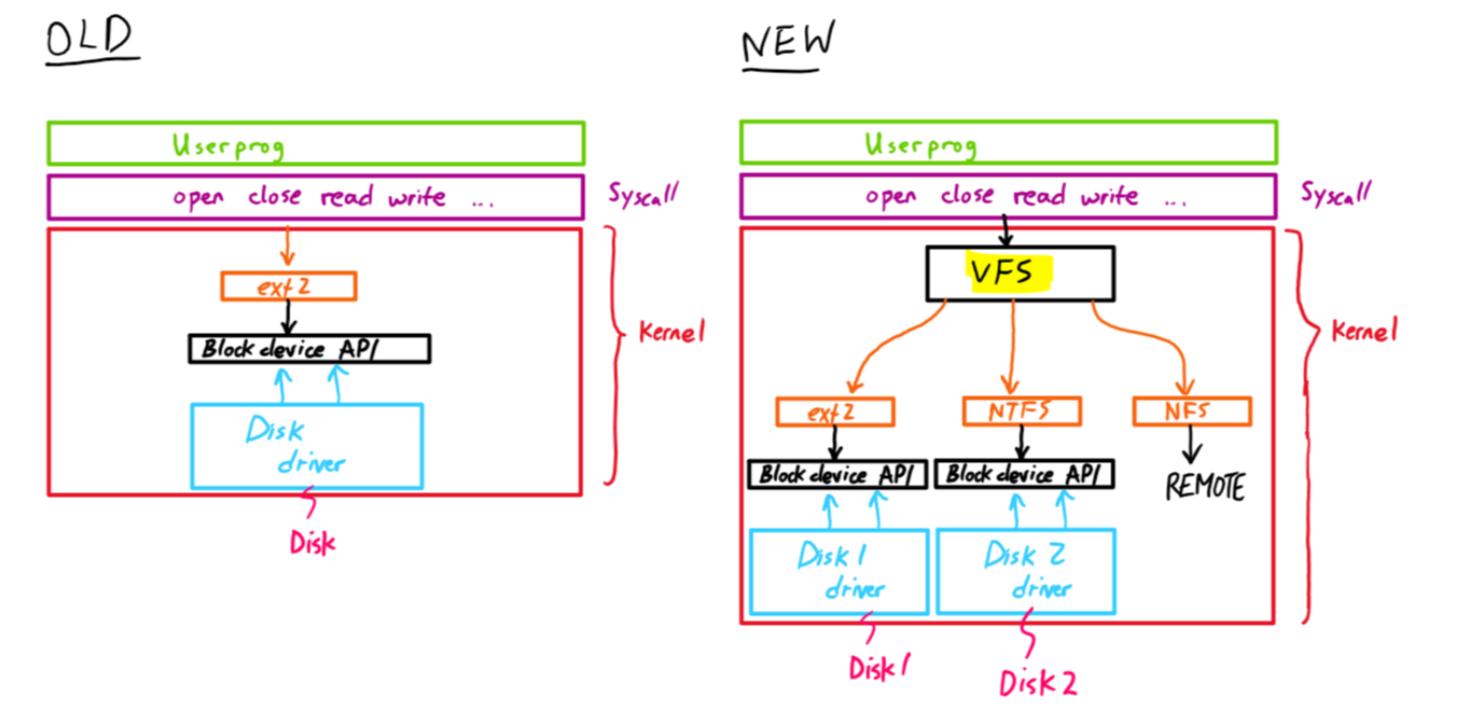

Distributed Filesystems #

Create an abstraction (virtual file system, VFS) that allows the system to interact with remote files as if they were local.

- NFS (network file system) translates read and write calls into RPC’s.

- These RPC’s are stateless and idempotent: they contain information for the entire operation.

- Results are cached on the local system. The server is polled periodically to check for changes.

- Write-through caching (writing all changes on server before returning to client) is used.

- Multiple writes from different clients simultaneously create undefined results.

End-To-End Argument #

The primary argument is that we can’t trust the network, so we need to guarantee services on both ends.