Reliability

In general, the network is best-effort, meaning that packets are not guaranteed to be delivered successfully. How do we build reliability on top of an unreliable network?

Semantics of correct delivery #

- At the network layer (L3 and below), delivery is best-effort. No guarantees can be made.

- At the transport layer (L4), delivery is at-least-once. Packets should reach the end host, but may be duplicated.

- At the application layer (L7), delivery is exactly-once.

The reliability goals of the transport and application layer are not guaranteed (since the underlying network can still fail)! However, reliability protocols must announce failures to the application, and never falsely claim a successful delivery.

Sending and receiving #

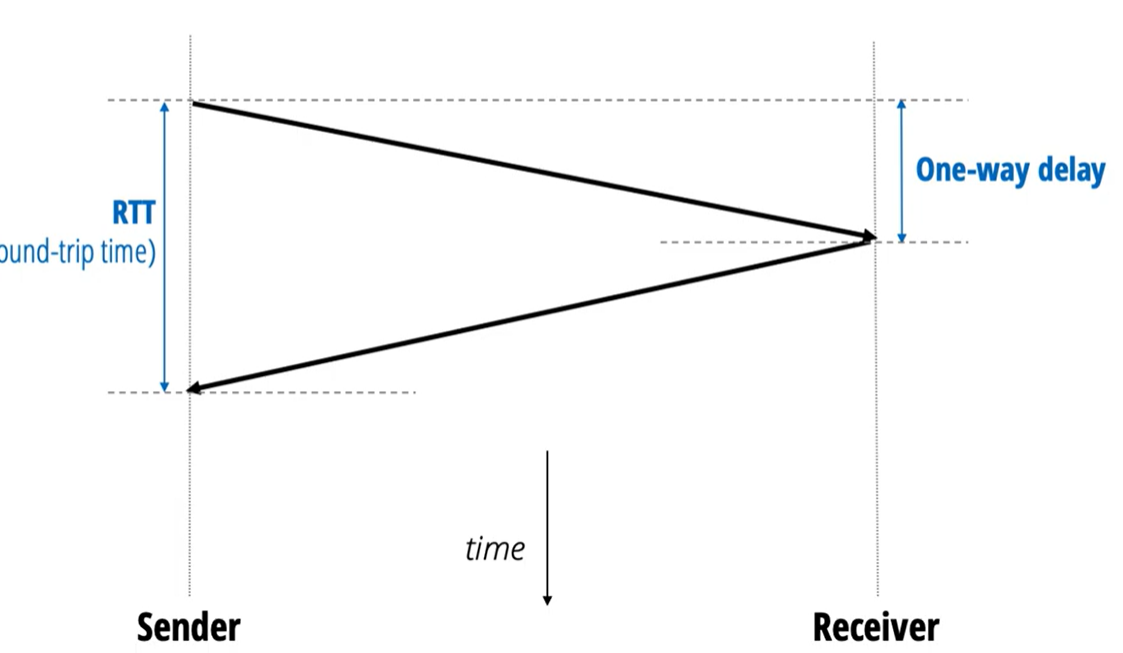

One way delay is the amount of time it takes for a packet to reach the reciever from the sender; Round trip time is the amount of time it takes for a packet to go both to and from the receiver.

One way delay is the amount of time it takes for a packet to reach the reciever from the sender; Round trip time is the amount of time it takes for a packet to go both to and from the receiver.

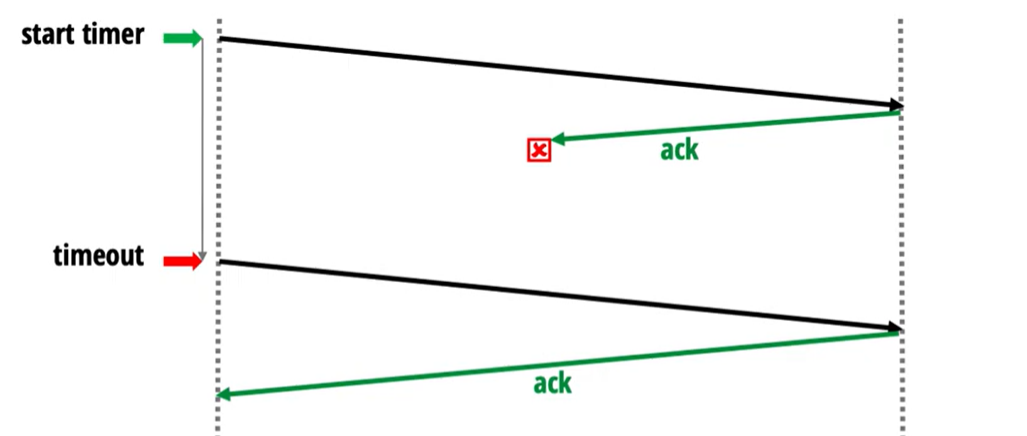

Packets can be duplicated in this example, where the acknowledgement message was lost and so the sender retransmitted the data:

An ack represents an acknowledgement of a successful receipt of a packet; a nack (negative ack) represents a failure message saying that the packet was corrupted.

Goals for reliable transfer #

Correctness: the destination receives every packet, uncorrupted, at least once Timeliness: data is transferred in a short period of time Efficiency: minimize use of bandwidth; avoid sending packets unnecessarily

In addition, we need to address all of the things that can happen to packets:

- Lost packets -> resend

- Corrupted packets -> send nack

- Delayed packets -> no issue due to at-least-once reliability

- Duplicated packets -> no issue due to at-least-once

- Reordered packets -> sequence numbers

Single packet case #

Algorithm #

Sender:

- send packet

- set timer (to some multiple of RTT)

- if no ACK is received when the timer goes off, resend the packet and reset timer

Building Blocks #

- Checksums are used to detect corruption

- Feedback is received in the form of acks/nacks

- Retransmissions address lost packets

- Timeouts let senders know when to resend packets

Multiple packet case #

Stop and wait protocol #

Use the single packet solution repeatedly, and wait until the ack for packet $i$ is received before sending packet $i+1$.

While this is correct, it is very slow and inefficient, with a max throughput of 1 packet per RTT. It is sometimes used when the RTT is very slow, such as internal communications between components in the same machine.

Flow Control #

Basic idea: the receiver tells the sender how much space it has left in an advertised window which is carried in the ACK. The sender will then adjust its window accordingly.

Window-based algorithms #

Allow multiple packets to be sent at the same time, and keep a window of packets in-flight with a maximum size of $W$. When an ack is received, remove that packet from the window, and allow the next one to be sent.

This achieves correctness and efficiency to some degree.

The value of $W$ should be picked to avoid overloading links (congestion control) and the receiver (flow control), while still taking advantage of the network capacity. In the ideal case where our network capacities our infinite, we should set $W$ to allow the sender to transmit packets for the entire RTT.

- Let $B$ be the minimum link bandwidth, and $P$ be the packet size.

- We want the sender to send at rate $B$ for the duration of the RTT to maximize efficiency.

- In reality we don’t usually want to use 100% of $B$ since the link is shared with other flows; the transport layer at the sender generally implements a congestion control algorithm to compute the desired bandwidth to use (congestion window).

- Therefore, set $W$ such that $W \times P \sim RTT \times B$.

- To address congestion control and flow control, set $W$ to be the minimum of the above, the congestion control window, and the advertised window.

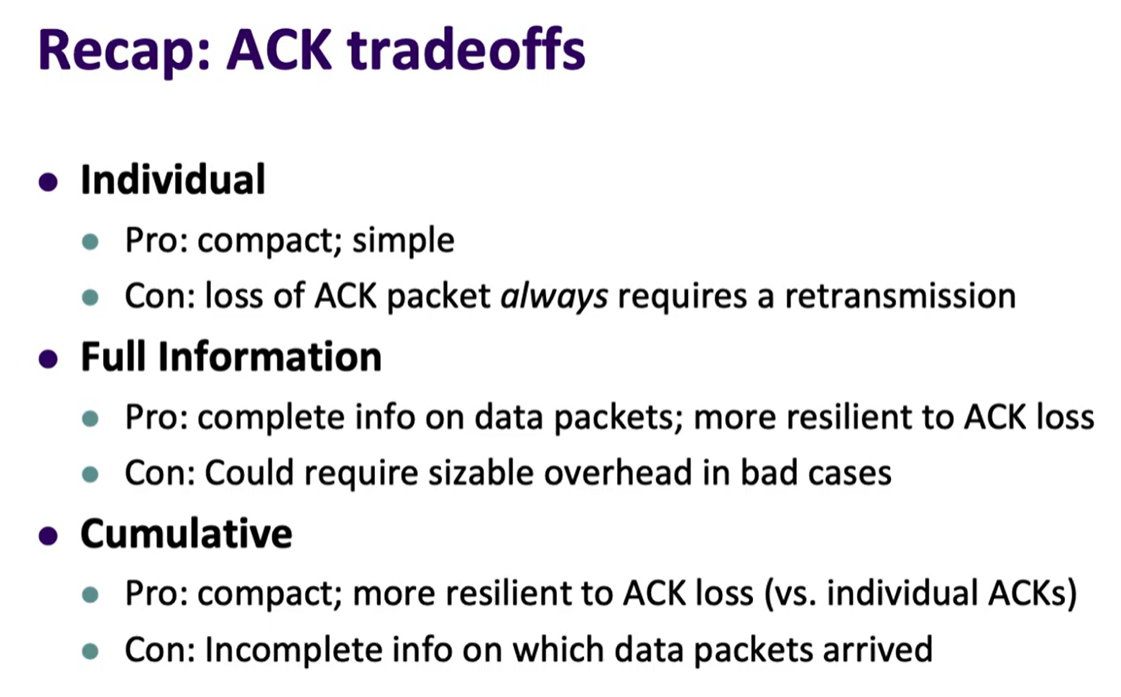

Full Information ACKs #

Rather than sending one ack corresponding to each individual packet, full information ACKs send two things:

- the highest number $n$ such that all packets with sequence number up to $n$ were delivered, and

- any additional packets (could have skipped some numbers after $n$).

Full information ACKs can get very long, so as a compromise we can just send a cumulative ACK with only the first of the two parts of the full information ACK. Cumulative acks tell senders how many packets to send, but not which ones to resend because they don’t tell the sender exactly which packets were received. For example, if the ACK “n <= 4” was sent 3 times, we know that a packet must have been lost, but it could have been any number greater than 4.

Go Back N #

Use window algorithm, but if an ack is not received, resend all $W$ packets in the window starting from the one that was lost.