Disks, Buffers, and Files

Relevant Materials #

Introduction #

Now that we’ve taken a look at how humans can interface with databases using SQL, let’s jump all the way down to the bottom and lay the foundations for how we can go from individual bytes to a fully functional database!

Before reading this section, review the page What is an I/O and why should I care? To reiterate the most important points from this section,

- An I/O occurs when a page is transferred between disk and memory (either read or written).

- Pages are always fetched in whole: it is impossible to read/write half of a page to memory.

- For the purposes of this class, a “block” and a “page” on disk are considered the same thing.

Summary

Disks are physical devices good at storing a huge amount of data.

Files are stored on the disk and represent one table.

Databases are collections of one or more tables.

Pages are the basic building block of files. A file is generally made up of many pages.

Records represent single rows in the table. Many records can be stored on the same page.When records from a database need to be accessed, they are copied from the disk to the buffer in memory one page at a time.

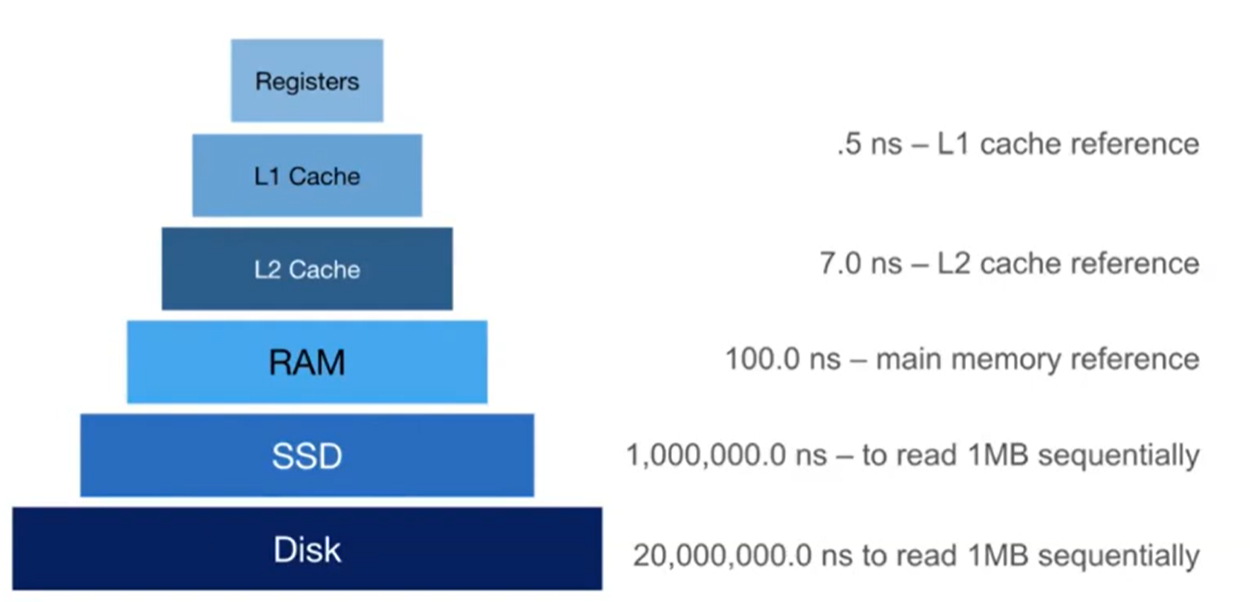

Devices #

Here’s the hierarchy of physical memory devices that modern computers use. The main tradeoff is price to speed: the devices higher up on the chart (like the cache) allow for far faster accesses, but are much more expensive to produce per unit of data compared to slow devices (like hard drives).

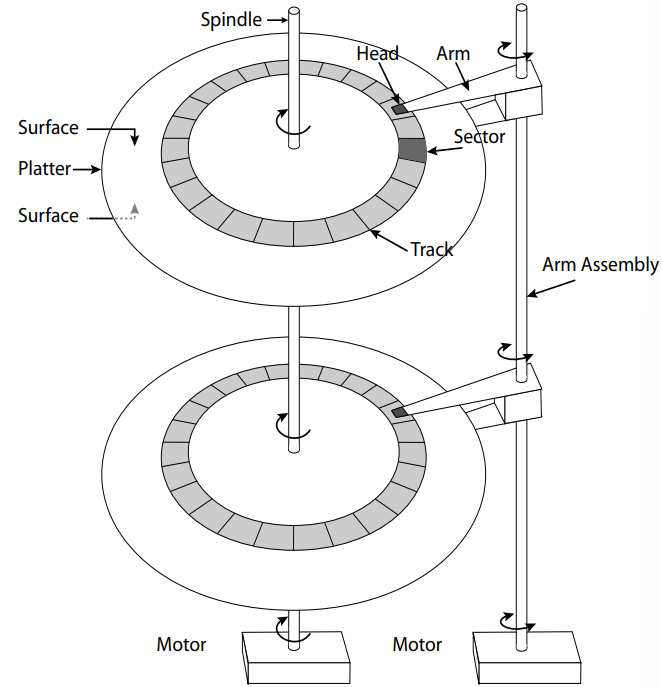

(Optional Context) The anatomy of a hard drive #

This section is taken from 61C. It’s not required knowledge for 186, but it helps develop an intuition for what types of access patterns are faster than others on the disk. The main takeaway: disks are really slow.

Hard drives are magnetic disks that contain tracks of data around a cylinder. HDD’s are generally good for sequential reading, but bad for random reads.

Disk Latency = Queueing Time + Controller Time + Seek Time + Rotation Time + Transfer Time

- Queuing Time: amount of time it takes for the job to be taken off the OS queue

- Controller Time: amount of time it takes for information to be sent to disk controller

- Seek Time: amount of time it takes for the arm to position itself over the correct track

- Rotation Time (rotational latency): amount of time it takes for the arm to rotate under the head (average is 1/2 a rotation)

Disk space management:

- provides an API to read and write pages to device

- Organizes bytes on disk into pages

- Provides locality for the ‘next’ sequential page

- Abstracts filesystem and device details

Files #

A Database file (DB FILE) is a collection of pages, which each contain a colection of records. Databases can span multiple machines and files in the filesystem (we’ll explore this idea more in Distributed Transactions.

There are two main types of files: heap files, which are unordered, and sorted files, in which records are sorted on a key. As you could imagine, sorted files add a significant amount of complexity in exchange for possibly faster runtimes. In general, range selections and lookups are faster in sorted files, while insertions, deletions, and updates are faster in heap files.

File Cost Analysis #

In order to make efficient queries, we need a measure of how good or fast a query is. Knowing that queries operate on records, which are stored on pages in a file on disk, we can use the following cost model for analysis:

- $B$ = number of data blocks (pages) in file

- $R$ = number of records per page

- $D$ = average time to read or write disk page (i.e. cost of one I/O)

For analysis, we will use the following assumptions:

- We are mostly concerned about the average case.

- The workload is uniform random.

- Inserts and deletes operate on single records.

- Equality selections will have exactly one match.

- Heap files always insert to the end of the file.

- Sorted files are always sorted according to search key.

- Packed files are compacted after deletions.

As an exercise, think about what might happen to the runtime if we try to remove each of these assumptions.

| Operation | Heap File | Sorted File | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scan all records | $B*D$ | $B*D$ | Full scan = need to access every page in the file |

| Equality Search | $B/2$ (average) | $\log_2(B) * D$* | Heap: on average, need to go through half the file Sorted: Binary search runtime |

| Range Search | $B*D$ | $(\log_2B + P)*D$ | Heap: no guarantee on location of elements in desired range Sorted: binary search to find start of range; range is $P$ pages long |

| Insertion | $2D$ | $(\log_2B + B) * D$ | Heap: read last page, then write page Sorted: find location (binary search), then insert and shift rest of file |

| Deletion | $(B/2 + 1) * D$ | $(\log_2 B + B) * D$ | Heap: need to find page first, then write it back (hence the +1) Sorted: find location (binary search), then delete and shift rest of file |

Heap File Implementation #

There are two approaches to actually implementing heap files.

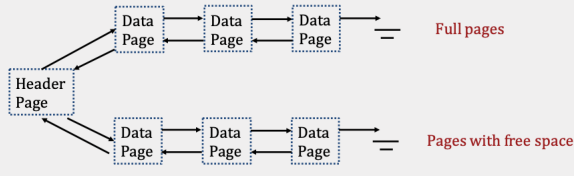

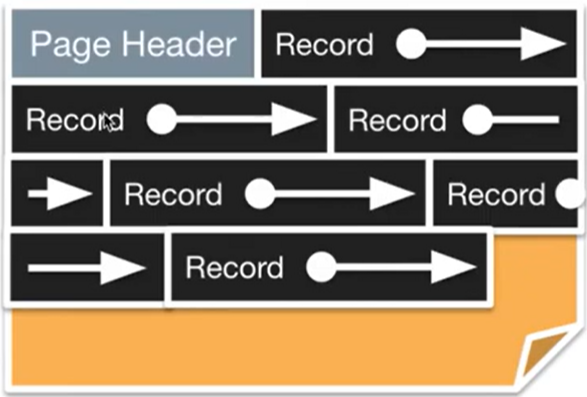

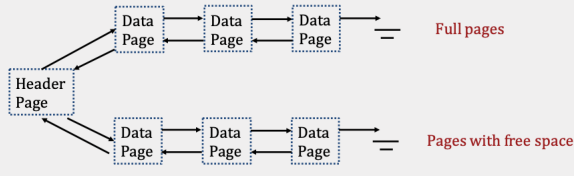

Linked List #

The first is the linked list implementation, where we have two linked lists: one of full data pages, and one of pages that still have free space. To insert a value into the file, we can ignore all of the full pages and just traverse the free pages, stopping at the first page that has enough free space to support the insertion.

You can find a common problem relating to heap files in the Practice Problems section.

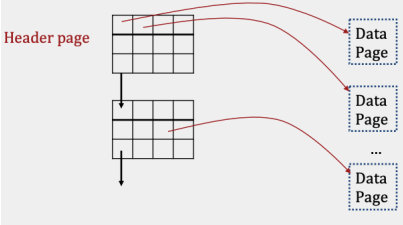

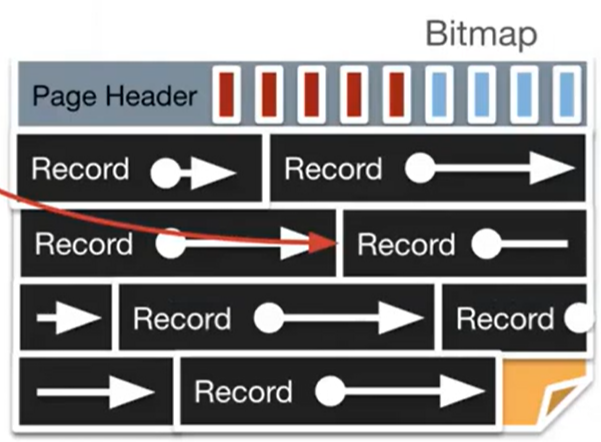

Page Directory #

The second type of heap file is a page directory implementation. Here, instead of a linked list of data pages, we’ll store a linked list of header pages:

Each header page then contains a list of pointers to data pages, as well as a pointer to the next header page.

Each header page then contains a list of pointers to data pages, as well as a pointer to the next header page.

Sorted File Implementation #

Don’t worry too much about this. We’ll explore a better way of maintaining sorted order when we discuss index files in B+ Trees.

Records #

Fixed vs. Variable Records #

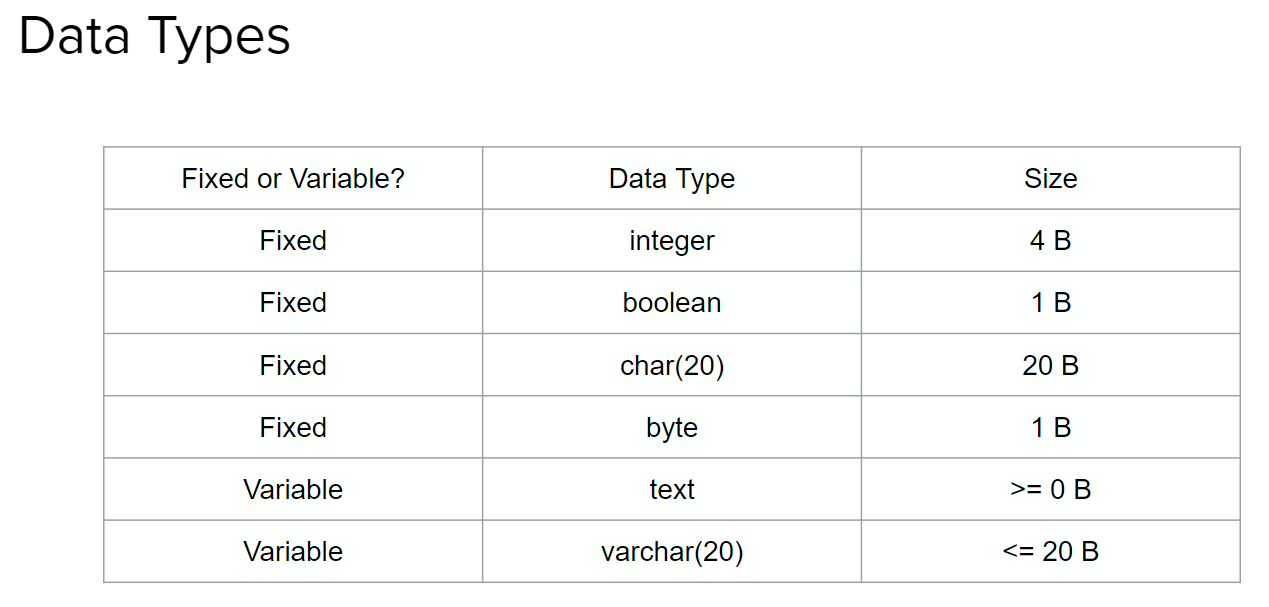

Fixed length records have a constant, known length. An example is integers, which always have 4 bytes.

- Field types are the same for all records, so just store the type information in memory. Variables can be accessed in the same location every time.

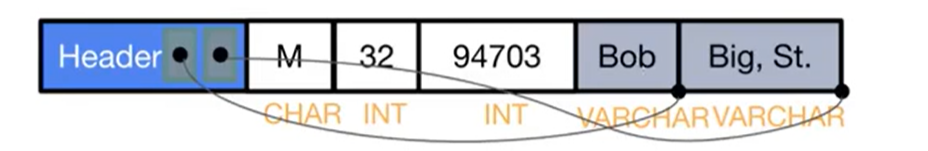

Variable length records may change in size depending on the data that is stored. An example is text, which could be 0 or more characters long. Here’s how we implement them:

- Move all variable length fields to the end of the record:

- Create a header in the beginning to point to the end of variable length fields (compute beginning based on presence of other variables).

Data File Implementations #

So, how do we actually store the records inside data pages?

First, every data page needs a page header. This header includes metadata like free space, number of records, pointers, bitmaps, and a slot table for which parts of the file are empty.

If records are fixed length, we can pack them densely, which maximizes the amount of data we can store on each page.

- We can easily append new records, but to delete, we would need to rearrange the records that come after the deleted record, which can get expensive.

We can also have unpacked fixed length records:

- To do this, we will:

- Keep a bitmap of free and empty slots in the header (one bit for each slot, rounded up to the nearest byte).

- To add, find an empty slot in the bitmap and mark it as filled.

- To delete, just flip the bitmap reference to 0. Don’t worry about modifying the data itself, since it’ll be overwritten eventually.

For variable length records, we use slotted page records:

- Relocate the page header into the footer. (This will allow for the slot directory to be extended.)

- In the footer, store pointers to free space containing the length and pointer to the next record.

- This can be prone to fragmentation (will need to be addressed somehow).

- This can also be used for fixed length records to handle null records

Calculating Record Size #

Records consist of atomic values like ints and chars. Typically, records also include pointers (depending on implementation) as well as variable length records.

For a standard record in a linked list, the following is required:

- $N$ bytes for each variable, where $N$ is its size in the chart above

- One 4-byte pointer in the header for every variable length record

- If nullable, each non-primary key takes 1 bit in the bitmap. Make sure to round up to the nearest byte.

- If using a slotted page implementation for variable length records, we’ll need 8 additional bytes in the header (free pointer, slot count) and 8 additional bytes in every record (record length, record pointer).

The maximum number of records that can be stored in a page is equal to the page size divided by the minimum record size, rounded down to the nearest integer.

- For slotted page, it would be the floor of (page size - 8 bytes) / (min record size + 8 bytes) due to the additional metadata needed.

The slot directory in a slotted page implementation has the following items:

- slot count (4 bytes)

- free space pointer (4 bytes)

- (record pointer + record size) tuple for every record (8N bytes)

Practice Problems #

Suppose you have a linked list implementation illustrated in the image above (3 full pages, and 3 pages with free space). In the worst case, how many I/Os will it take to insert a record into a free page? Assume there is enough space in an existing page in the file.

5 I/Os. Here’s the walkthrough- each step incurs one I/O:

- Read the header page to find the pointer to the first free page.

- Read the first free page, and realize that it doesn’t have enough space! Luckily, it has the pointer to the second free page in it.

- Read the second free page. The same thing occurs.

- Read the third free page. Due to the problem statement we can assume that our data will fit here! So we will update the third page to insert the new data.

- Write the updated page back to disk.

7 I/Os. In the worst case, all data pages are full, and all header pages are also full except for the very last one. So, the following must happen:

- Incur 5 I/Os reading each of the 5 header pages. Since the page directory implementation stores metadata about whether data pages are full or not, we don’t have to actually read in the data pages.

- Create a new data page, and write it to disk, incurring 1 I/O.

- Update the last header page with a pointer to the new page, incurring 1 I/O.

Suppose we have the clubs table from the previous section:

CREATE TABLE clubs(

name TEXT PRIMARY KEY,

alias TEXT,

members INTEGER

);

What is the maximum number of records that can fit on a 1 KiB (1024 byte) page, assuming all fields are not null?

50 records.

The maximum number of records is achieved when each record is as small as possible. This occurs when both of the text variables have a length of 0. So the smallest record contains:

- 4 byte pointer to

name, - 4 byte pointer to

alias, - 4 byte integer

members.

In total, each minimum-size record is 12 bytes long. However, each record also requires a pointer and a record length value to be stored in the footer (4 bytes each), meaning each record effectively takes 20 bytes in the page.

The slot directory always contains the slot count and free space pointer (4+4 = 8 bytes), so let’s subtract 8 bytes from 1024 to get 1016 bytes remaining for use for records.

Finally, let’s divide 1016 by 20 to get the number of records that can fit: $$\lfloor 1016/20 \rfloor = 50$$