Proofs

Introduction #

A proof is a set of logical deductions that can be used to show how something is true. This is powerful because proofs can often be very general, allowing a truth to be used in a whole bunch of cases that don’t individually need to be re-proven.

There are a number of common proof techniques (although these certainly aren’t exhaustive!) outlined below.

Direct Proofs #

In direct proofs, we can use the definitions directly to show that something is true. No trickery here, just straightforward navigation from point A to point B.

Direct Proof Form:

- Goal: $P \iff Q$

- Assume P.

- Do a bunch of steps using the definitions and assumptions created by the values and operators used.

- Therefore Q.

Example:

Let $D_3$be the set of 3 digit natural numbers. Show that for all $n \in D_3$, if the alternating sum of digits of $n$is divisible by 11, then $11 \mid n$. (Lecture 2)

- First, let’s make sure this makes sense. Let’s try some examples:

- if $n=605$, then $n$is divisible by 11. Its alternate sum is $6 - 0 + 5 = 11$. $11$is indeed divisible by 11, so this looks like it could be true!

- Next, let’s write this in propositional logic:

- $\forall n \in D_3, (11 \mid$ alt sum of digits of n $) \implies 11 \mid n$

- Now, let’s try to prove it starting with assuming that all $n$ are 3 digit natural numbers.

- Let $a, b,$and $c$ represent the three digits of $n$such that $n = 100a + 10b + c$.

- If the alternating sum of digits is divisible by 11, then $11 \mid a - b + c$.

- Using the definition of division, $a - b + c = 11k$for some natural number k. We’re trying to prove that $n = 100a + 10b + c = 11m$ for another integer $m$ as well!

- Solve for $c$using the alternating sum to get $c = 11k + b - a$. Substitute this value into the second equation to get $100a + 10b + 11k + b - a = 11m$. Simplifying, this equation is equivalent to $99a + 11b + 11k = 11m$.

- We know that this must be true because each individual term is multiplied by a number divisible by 11. Therefore, the entire number must also be divisible by 11.

Proof by Contraposition #

As a reminder, the contrapositive of a statement $P \implies Q$is $\lnot Q \implies \lnot P$. These two statements are logically equivalent! Sometimes, it’s easier to prove the contrapositive, which would in turn prove the original statement.

Contraposition Form:

- Goal: $P \implies Q$

- Assume $\lnot Q$.

- Do a bunch of steps using another type of proof.

- Therefore $\lnot P$.

Example:

For every $n \in \mathbb{N}, n^2$ even $\implies n$ even

- If we try proving using a direct proof, we’ll have to deal with the squared term (and square roots)! This might get nasty; we’d rather deal with the nicer right side.

- First, let’s find the contrapositive of Q. Q is “n is even”, so the contrapositive is “n is odd”.

- Then, let’s find the contrapositive of P. P is “n squared is even”, so the contrapositive is “n squared is odd”.

- Let’s use the definition of an odd number ($n = 2k + 1$for some natural number k) to work through this.

- If $n = 2k +1$, then $n^2 = 4k^2 + 4k + 1$ = $2(2k^2 + 2k) + 1$.

- Since this is also the form of an odd number, $n^2$must be odd!

Proof by Contradiction #

Instead of proving that $P$is true, maybe we could show that $\lnot P$makes no sense at all! (We know that if $\lnot P$is false, then $P$must be true.)

Contradiction is a great choice for proving things that have infinitely many cases (since you can just prove the opposite, which is finite!).

Contradiction Form:

- Goal: $P \implies Q$

- Assume $\lnot P$.

- Do some steps here.

- Therefore, $\lnot P$is a contradiction.

Example:

Show that there are infinitely many prime numbers.

- First, let’s assume the opposite - that there are a finite number of prime numbers, which can be represented by the set ${ p_1, \cdots, p_k}$.

- Let’s define a number $q = (p_1 \times p_2 \cdots \times p_k) + 1.$

- Since $q$is larger than any prime number in our set, it can’t be a prime number by our assumption.

Note that we did not prove that$q = (p_1 \times p_2 \cdots \times p_k) + 1$is a prime number! This is because we started with a false statement, so everything in the middle of a contradiction proof cannot be generalized to true statements.

Proof by Cases #

Sometimes, we can break a statement down into smaller cases and prove each one individually. These cases could be something like “a is odd” and “a is even”, where it is impossible for any other case to be true. If all possible cases are proven, then the entire statement is then proven.

Example:

Show that there exists an irrational x and y such that $x^y$is rational.

- First, let’s find some cases. The two cases could be that $x^y$is rational or $x^y$is irrational. If $x^y$is rational (the first case is true), then we’re done! But if the second case is true, then we’re back to where we started.

- Since all we need to do is show existence, we can choose any irrational number for x and y. $\sqrt{2}$seems like an easy choice!

- $\sqrt{2}^{\sqrt{2}}$is irrational, but what about $(\sqrt{2}^{\sqrt{2}})^{\sqrt{2}}$? That’s just $2$!

Proof by Induction #

Induction is great for proving that something is true for everything in a set (often the natural numbers). If we prove the first value, then prove that the next value is true, then the value after that is also true, and so on.

This can be likened to the domino effect. If the first one’s true, then it knocks down the domino for the next value. If that’s true, then it knocks out the next one, and so on until every possible value is covered.

Induction Form

- Prove P(0). (Base case)

- Assume P(k). (Induction Hypothesis)

- Prove P(k+1). (Induction Step)

- When proving the induction step, we can treat the induction hypothesis as a true statement!

Example: The Two Color Theorem

Here’s a visually intuitive example of induction in action!

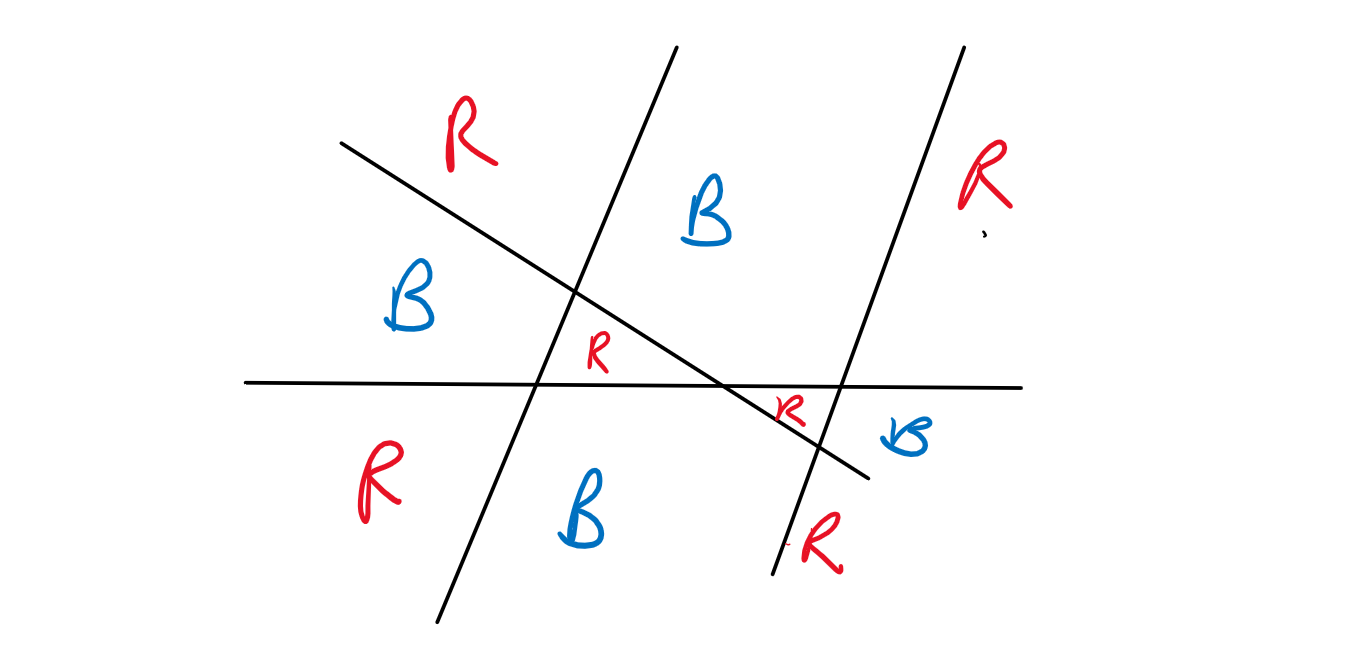

The Two Color Theorem states that for any collection of intersecting line segments, the regions that they divide can be assigned one of two colors such that a line never has the same color on both sides.

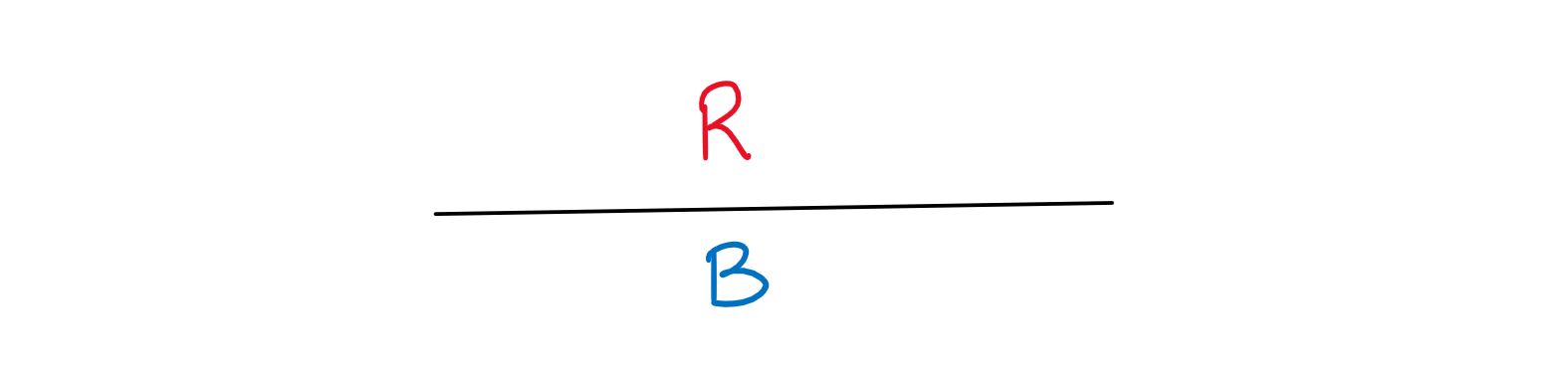

In order to prove this, let’s start at the base case, where there is only one line:

Here, it’s pretty clear that it is indeed possible to put a different color on each side of the line, in this case let’s just choose blue and red.

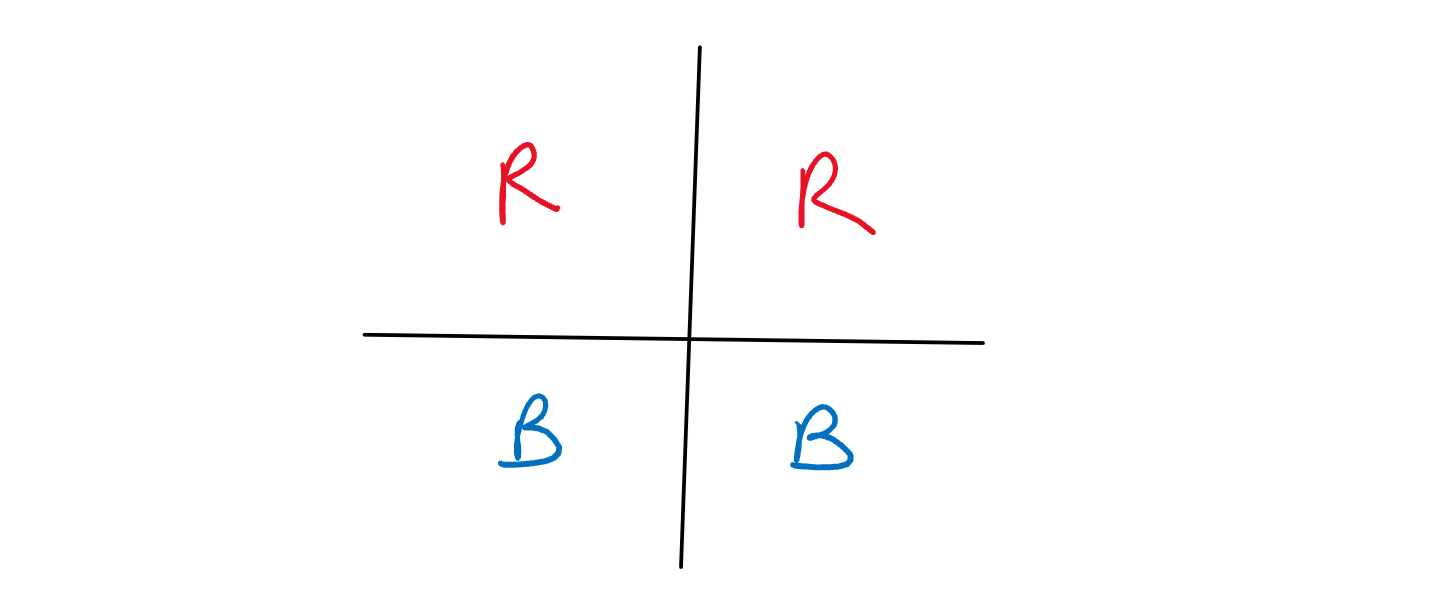

Now, let’s see what happens when we add a new line:

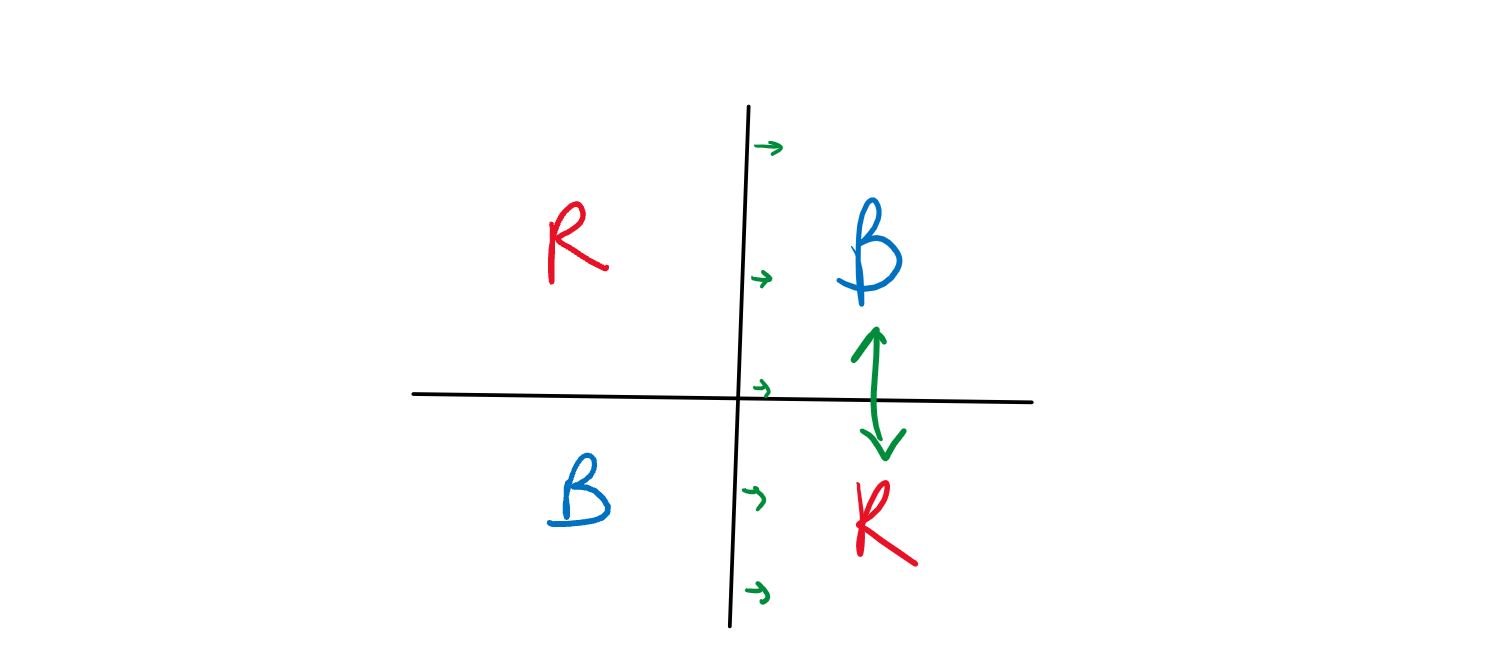

Looks like we have a conflict now! The blues on the top and reds on the bottom are touching. However, it’s not too hard to fix this. Let’s just flip the blue and red on one of the sides:

It turns out that this process: drawing a new line and flipping all of the colors on one side, works in any configuration of lines! This is because of the fact that flipping the colors on one side of a line doesn’t affect whether or not those colors are alternating.

Stronger Induction #

Sometimes, an inductive proof can be rather elusive. It might be easier to make the statement stronger and prove that instead! (It should make sense that a stronger argument means that a weaker argument is also true.)

For example, take the statement “The sum of the first n odd numbers is the square of a natural number.”

As we try to figure out a pattern, we might notice something:

For n = 1: $1 = 1^2 = n^2$

For n = 2: $1 + 3 = 2^2 = n^2$

For n = 3: $1 + 3 + 5 = 3^2 = n^2$

Wow, looks like not only is the sum equal to some arbitrary square number, but it’s actually equal to $n^2$! It’s a lot easier to prove this fact than the original one, and proving this completely includes the original statement.

Another (aptly named) principle that might come in handy is the Strong Induction Principle! This principle is useful for when you don’t want your base case to be $0$. The Strong Induction Principle states that if we prove all of the propositions from P(0) up to P(k), then P(k) can be used as a base case:

$(\forall k \in \mathbb{N})((P(0) \land P(1) \land \cdots \land P(k)) \implies P(k+1)) \implies (\forall k \in \mathbb{N})(P(k))$

Proof of the Induction Principle #

$(\lnot \forall n)P(n) \implies ((\exists n) \lnot (P(n - 1) \implies P(n))$

The Well Ordering Principle states that for all subsets of natural numbers, there exists a smallest number in that subset.

- This is not trivial! Think about rational numbers- it’s impossible to get the smallest rational number because it extends to $-\infty$.

- This principle justifies the use of induction for any set of natural numbers. If the smallest number (base case) always exists, then we can just prove that and move upwards, rather than trying to prove both $k-1$and $k+1$.

More Resources #

Note 2: https://www.eecs70.org/assets/pdf/notes/n2.pdf

Note 3: https://www.eecs70.org/assets/pdf/notes/n3.pdf

Lecture 2 Slides: https://www.eecs70.org/assets/pdf/lec-2-handout.pdf