Chapter 3: Threads

The Thread Abstraction #

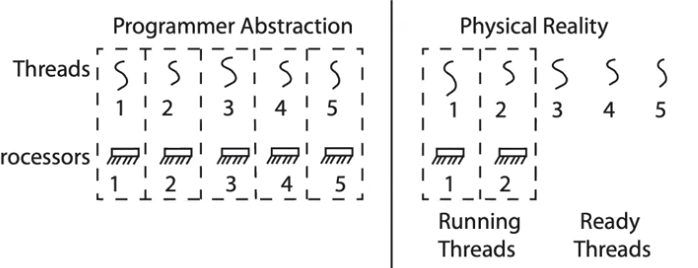

A thread is a single unique context, or unit of concurrency, for execution that fully describes the program state. A thread consists of a program counter (PC), registers, execution flags, and a stack.

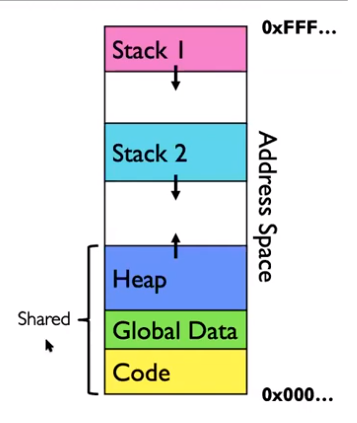

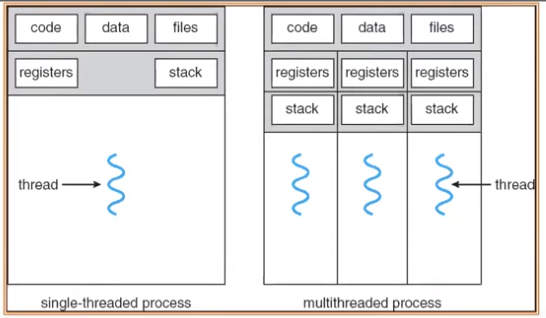

- All threads in the same process share the same code, data, and file access, but each has its own register state and stack.

- Certain registers hold the context of the thread (such as the stack pointer, heap pointer, or frame pointer).

- A thread is executing when the processor’s registers hold its context

- Having multiple threads allows the OS to handle multiple things at once (MTAO). This is essential for networked servers with multiple connections, parallel processing for performance, user interface responsiveness, and many more modern computing applications.

Each thread has a private state stored in the Thread Control Block (TCB). Additionally, each thread has a dedicated portion of the stack that is isolated from other threads:

Thread States #

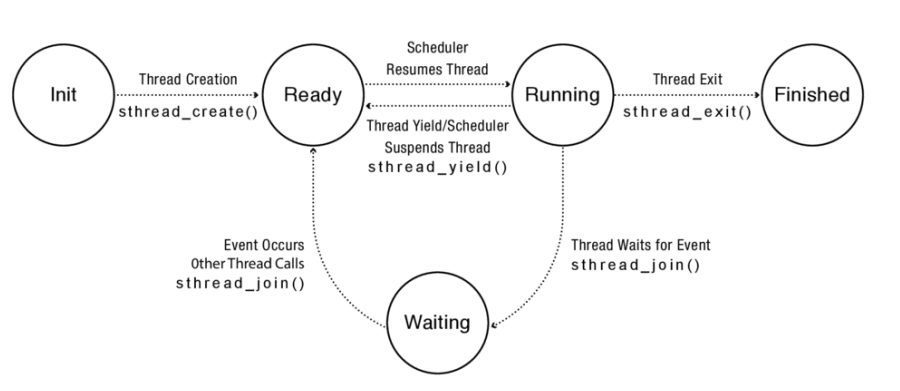

Operating systems have a thread scheduler that manages multiple threads, and can switch between ready and running threads. Threads can have one of several states:

Running: current being executed

Ready: can run, but not currently running

Blocked: cannot run. This typically occurs when thread is waiting for I/O to finish. When the I/O is complete, it becomes ready. As a result, I/O latency can be masked by multithreading (since other threads can run in the meantime).

The thread lifecycle, from initialization to completion.

Multithreaded Programs #

By default, C programs are single-threaded (and when you create a new process, it only has one thread).

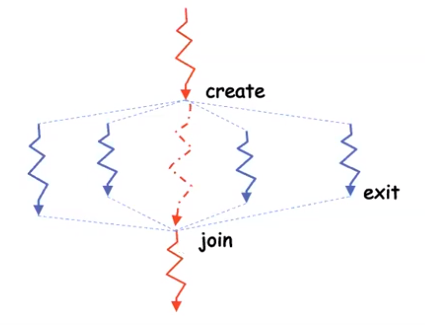

One common method of turning a single-threaded program into a multi-threaded program is through fork-join parallelism. Using this paradigm, the main thread creates child threads, and when children exit they join back with the main thread.

UNIX Thread Management #

Fork-Join Parallelism #

The function int pthread_create(pthread_t *restrict thread, const pthread_attr_t *restrict attr, void *(*start_routine)(void *), void *restrict arg) can be used to create a thread.

- Create and immediately start a new thread in the same address space (i.e. sharing the same variables and references as the parent thread).

- Saves the thread ID (tid) into the value pointed to by

*thread. - Pass in the arguments pointed to in

*argto the function specified instart_routine. (The arguments should be cast into a(void *)type.) - Begin executing the

start_routinefunction.

The function int pthread_join(pthread_t thread, void **retval) can be used to join an existing thread back to the main thread. Calling this function will do the following:

- Make the parent thread wait until the specified

threadcompletes before continuing. - When the thread completes, save the exit status of the thread into the location pointed to by

retval. This can be set toNULLif the value is not needed.

If a child thread is complete, int pthread_exit(void *retval) can be called to terminate the thread early and return a result.

A context switch can be forced using pthread_yield, which causes the thread to relinquish the CPU and get placed at the end of the run queue.

Race Conditions #

Threads run in a nondeterministic order, so we must be careful to join them at the correct time. Here’s what happens if we don’t:

void *helper(void *arg) {

printf("%d", arg);

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t thread;

int* param = malloc(sizeof(int));

*param = 1;

pthread_create(&thread, NULL, &helper, (void *)(param));

printf("0");

return 0;

}

The above code could have multiple outcomes based on the order of thread execution:

helperruns first:10is printedmainprints, thenhelper:01is printedmainreturns beforehelpercan execute:0is printed

If multiple threads need to modify the same variable at the same time, then locking is required (this will be discussed further in the Concurrency section).