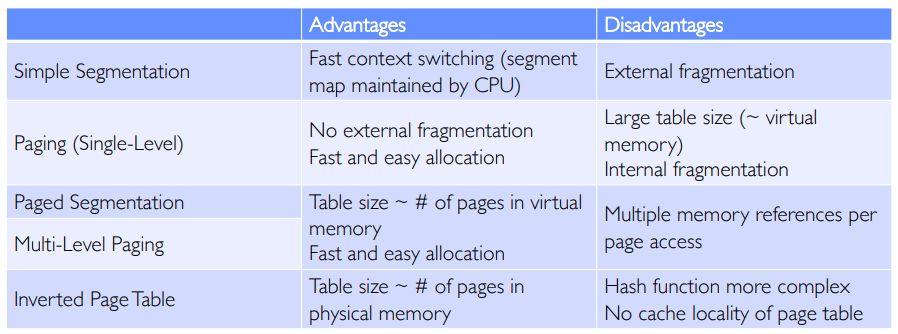

Chapter 7: Address Translation

Introduction #

Every modern computer has physical memory inside of it, that might look something like this:

Physical RAM modules typically contain anywhere from 4 to 128GB of memory (well, at the time of writing). However, there are only a few sticks of RAM, and possibly hundreds of processes that need to access them at the same time!

This is where memory management comes in. This chapter will cover several methods to do so, such as address translation (virtual memory) and paging (breaking memory into chunks).

Address Translation #

First, let’s solve one of the major problems: how do we allow many programs to share a single module of physical memory?

The TL;DR: virtual memory, or an illusionary space given to each program such that they think they’re the only one using the memory. Then, we can offload the work of translating virtual memory to physical memory to the kernel.

Goals of Address Translation #

An effective address translation scheme will have the following:

- Memory protection: prevent processes from accessing or overwriting memory it doesn’t own, such as from the kernel or other processes.

- Memory sharing: allow multiple processes to access shared sections of memory, if needed.

- Controlled overlap and flexible memory placement: although we should be able to give a process any chunk of physical memory, each process or thread should have its own separate state that do not collide with one another.

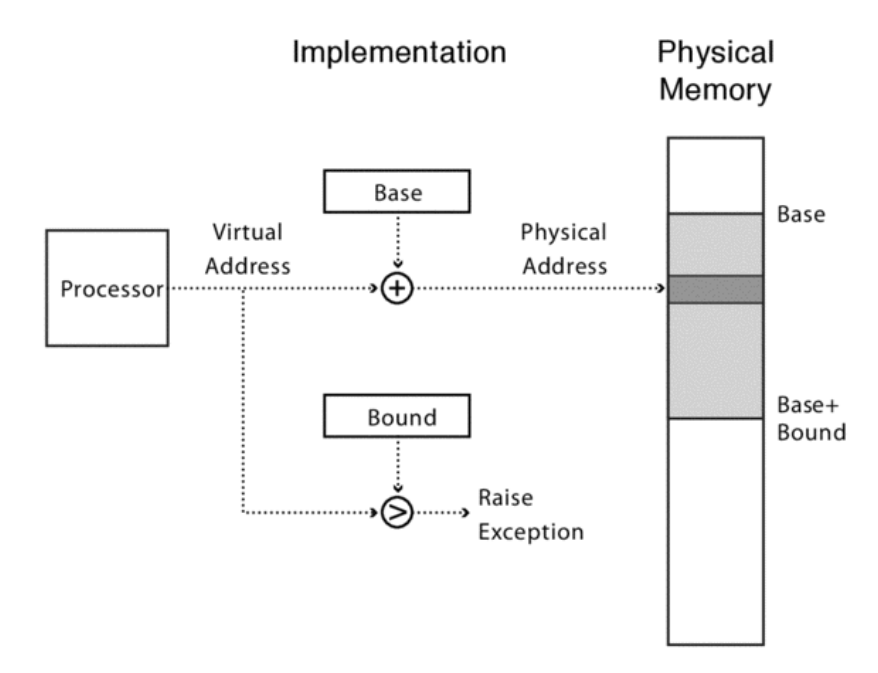

The Basics: Base and Bound #

Recall the simple base and bound scheme to map process memory to physical memory by adding a certain offset to each memory address:

Base and bound, while very easy to implement, has severe limitations. Notably, it does not allow for memory sharing, and dynamically growing memory regions like heaps or stacks are not supported.

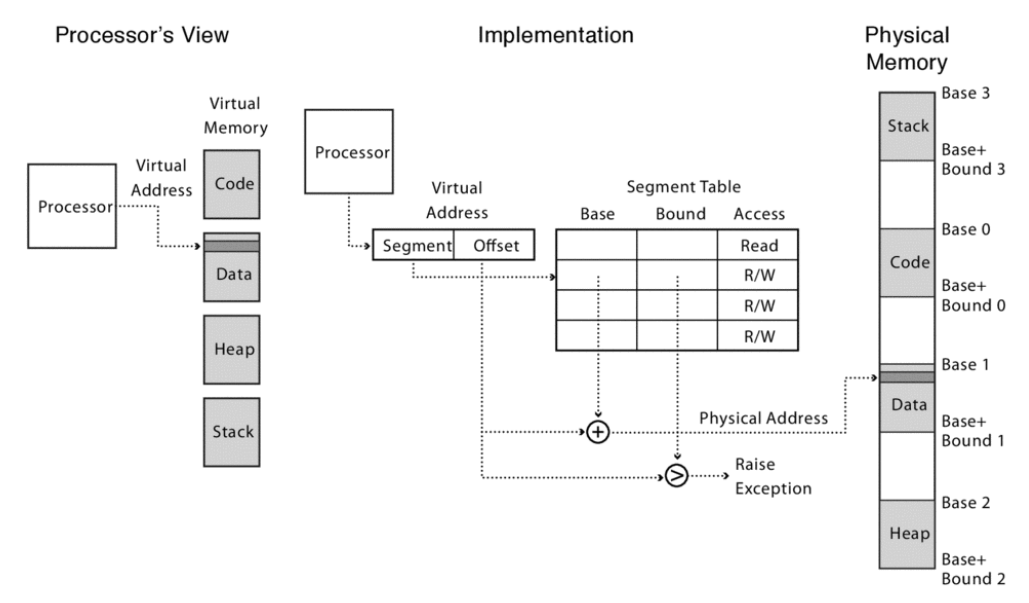

Segmented Memory #

The primary way we can fix these issues: segmented memory. Rather than only having one section of memory per process, we could split it up, such that a process’ memory is composed of many small chunks of physical memory!

Using segmented memory, we can more easily share memory (just give multiple processes a pointer to the same segment(s). Furthermore, if a growing data structure such as the heap starts to overflow onto another section, we can just work around that and set the next segment to point to an entirely different part of memory.

However, segmented memory still has its own limitations. The biggest problem is that of fragmentation, or wasted space in memory.

- External fragmentation refers to gaps between chunks.

- Internal fragmentation refers to the provisioning of large segments to only store a small amount of data, such that most of the segment is unused.

- Both are major issues of segmented memory.

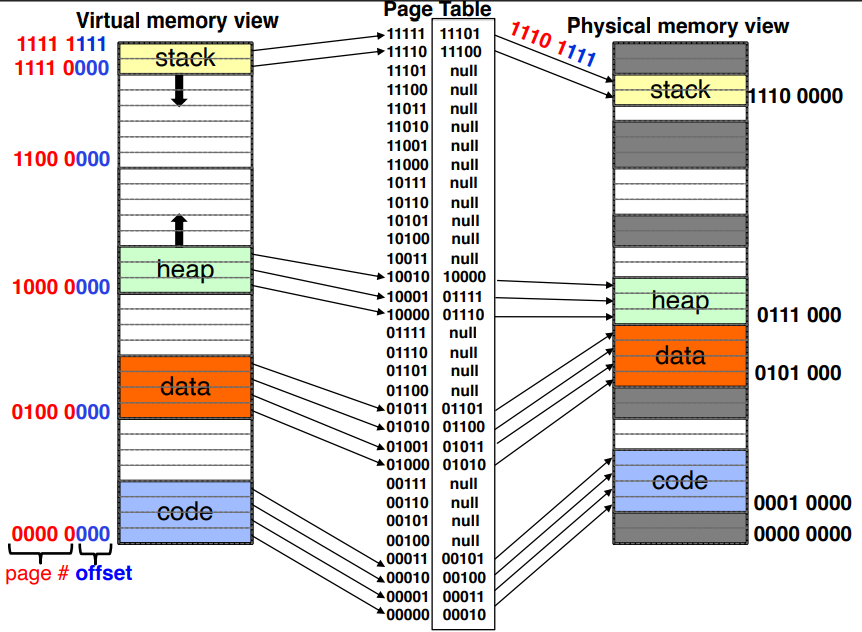

Paged Memory #

Let’s explore a third option of memory management, paged memory! Rather than a list of segments, each process will have fixed-sized page frames. This has multiple advantages:

- Page table entries can be much more compact compared to segment tables, because only the top bits need to be stored (the page size is a constant power of two, so we don’t need to keep storing those bits).

- External fragmentation is less frequent, because a page can always fit into an empty space in physical memory. Each page of physical memory can simply have a bit that flips when it becomes used, and turns back off when it gets freed.

- Support for security measures: address space layout randomization (ASLR), which adds a random space between memory segments (code, heap, etc.) and kernel address space isolation (kernel-only pages) can both be easily implemented.

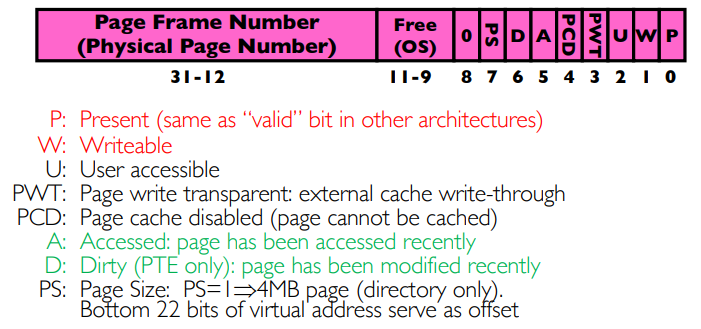

Page Table Entries #

Paging Mechanics #

Now, let’s get more specific about how paging can be implemented, and how to evaluate a particular paging scheme.

To get acquainted with the numbers we’ll be working with, here are a few typical sizes:

- Memory is usually around the order of (1GB) to (128GB).

- Page sizes are usually around 4KB ().

- Address spaces are either for 32-bit systems, or for 64-bit systems.

A simple page table will have one entry per page. So in a 32-bit system, we’d have number of entries, which is about 16MB of memory assuming each entry is 32 bits long.

And for a 64-bit system, the amount of memory needed to store the page table gets absolutely ludicrous (on the order of exabytes)! Luckily, there is a solution:

Multi-Level Page Tables #

Especially in 64-bit systems, we almost never need to use the entire address space. Thus, the address space is sparse (lots of empty memory in between used sections), and most of the page table entries will be pointing to unused areas.

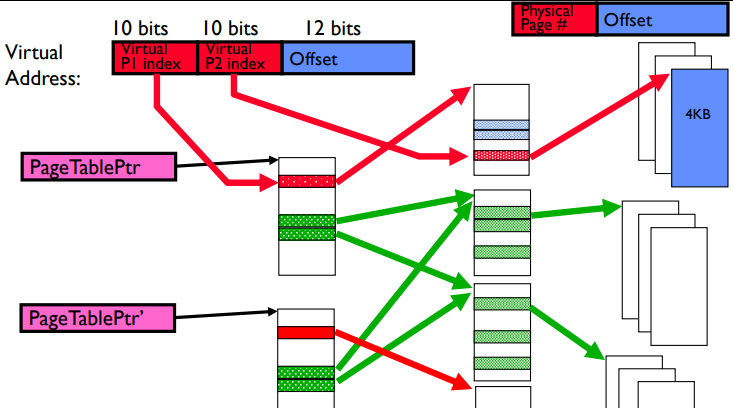

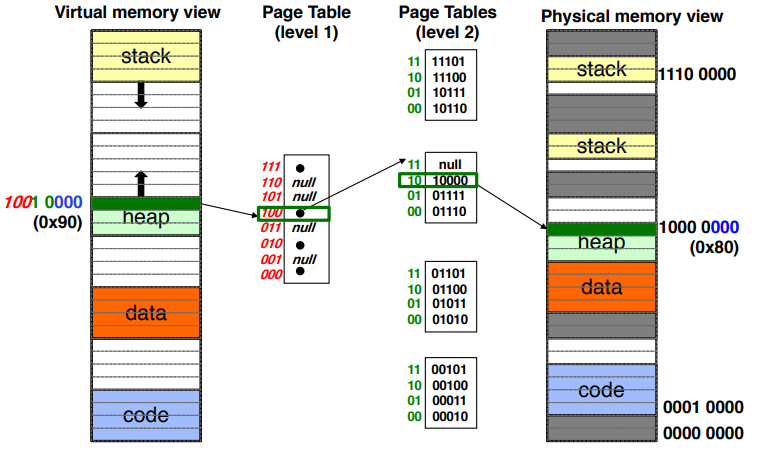

In order to mitigate the memory issue, we can make multi-level page tables where rather than just having one page table, we have tree of page tables where the first layer points to a page table in the second layer, and so on.

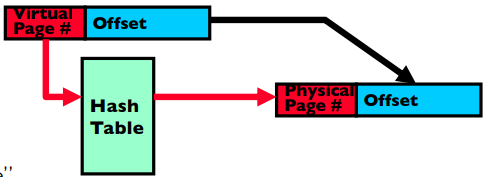

To make things even less memory-intensive, we can use inverted page tables which store mappings in a hash table structure rather than a tree structure. While more complex, this makes the size of the page table independent of the size of the virtual address space.

Address Translation: Summary #