B+ Trees

Relevant Materials #

- Note 4

- Discussion 3: view this for B+ tree algorithm walkthroughs!

Introduction #

B+ Trees are one type of index: a data structure that allows for quick lookups based on a particular key. They are very similar to binary trees, but can have more than two pointers and come with a variety of improvements.

What is an index exactly? #

We can index a collection on any ordered subset of columns.

In an ordered index (such as a B+ Tree), the keys are ordered lexicographically by the search key columns:

- First, order by the 1st column.

- If there are rows with identical values in the 1st column, sort them by the 2nd column.

- Continue until all columns are processed.

Composite Search Keys (optional context) #

Using a composite search key is one way to create an index on multiple columns. The composite search key on a set of columns matches a query if:

- the query is a conjunction of zero or more equality clauses:

k1 = v1 AND k2 = v2 .. k_m = v_m

- and at most 1 range clause:

- either or

Intuitively, a composite search key matches a continuous range of rows in the lexicographically sorted table.

The Representation #

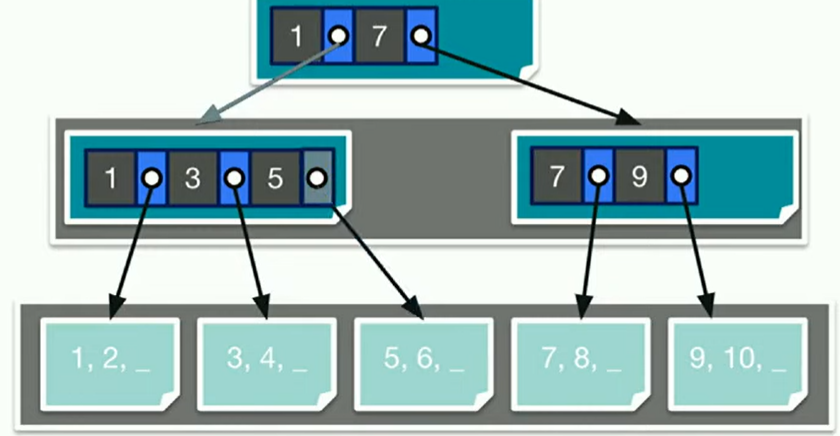

There are two types of nodes in a B+ Tree.

- Inner nodes make up all but the last layer of the tree, and store Key-Pointer pairs that reference more nodes.

- Leaf nodes make up only the last layer of the tree, and store either records themselves or references to the records.

You can think about each node being data that is stored on one page. So, when we want to access data in a B+ tree, we’ll have to incur one I/O for each node that we read or write. We can assume that the fan-out is small enough such that this will always be true.

The height of a tree is defined as the number of pointers it takes to get from the root node to a leaf node. For example, it would take 3 I/Os to access a leaf node for a height tree (read root node, read inner node, read leaf node).

All entries within each node are sorted. All B+ trees must follow the two invariants below to guarantee nice properties:

Key Invariant #

For any value in an inner node, the subtree that its pointer references must only have values greater than or equal to .

Occupancy Invariant #

The order of the tree, , is defined such that each interior node is at least partially full: where is the number of entries in a node. In other words, every node must have at least entries and at most entries.

The fan-out is equal to . (This is the max number of pointers in each node.) The amount of data a B+ tree can store grows exponentially based on the fan-out factor: where is the fanout and is the height of the tree.

At typical capacities (fan-out of 2144), at a height of 2 the tree can already store records!

Operations #

Insertion #

B+ Tree insertion is guaranteed to maintain the occupancy invariant.

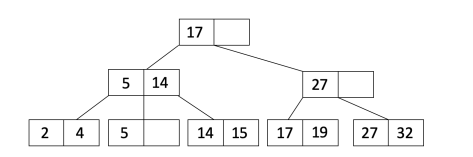

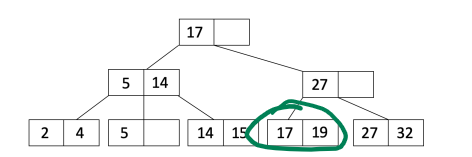

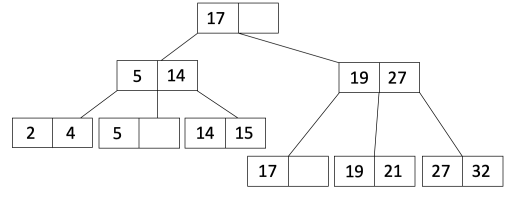

For the following steps, we will use the example of trying to insert the value into the tree below:

Find the leaf node where the value should go (using binary search):

If the leaf node now has more than entries:

- Split the leaf node into two leaf nodes and with and entries, respectively.

b. Copy the first value of into the parent node and adjust pointers to include and .

If the parent is now overflowed, then recurse and do the algorithm again. But this time, instead of copying the first value, we will move it instead (doesn’t stay in the original node).

Deletion #

In practice, the occupancy invariant is often not strictly enforced. This is because rearranging the tree is less efficient than having a good-enough approximation.

Therefore, for B+ Tree deletion, just identify the leaf node that contains the desired value to delete, and simply remove it. Nothing else needs to be done.

This is acceptable in practice because it is usually far more common to insert values into a B+ tree than it is to delete them, and insertions will restore the occupancy invariant quickly.

The Three Alternatives #

There are three ways to implement B+ trees that we’ll explore in this class. Note that in Project 2, we will create an Alternative 2 B+ tree implementation.

Alternative 1 #

The first alternative is to store records directly in the leaf nodes. This allows faster access to the data, but is very inflexible in the case that we want to build an index on another column (we’d have to copy over all the data to another B+ tree).

Alternative 2 #

The second alternative is to store pointers to data pages in the leaf nodes, which then store the records. This solves the inflexibility issue of Alt. 1, but will need to incur an additional I/O

Alternative 3 #

The third alternative stores a list of pointers to matching record locations in the leaf nodes. This allows us to use less data if storing many duplicate entries, but comes at the cost of additional complexity.

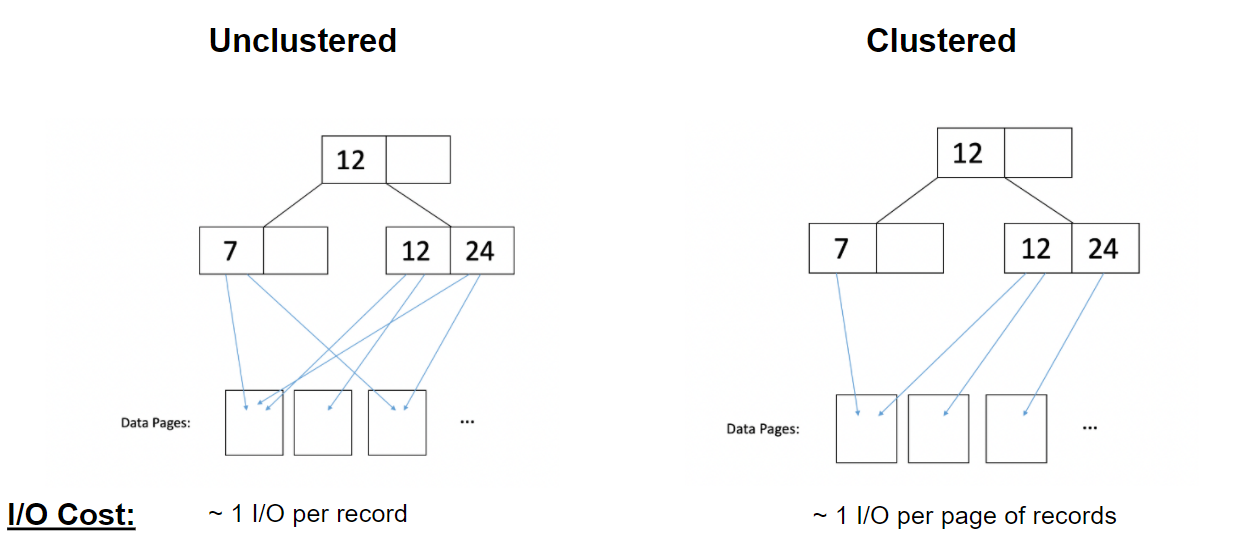

Clustered Indexes #

In a clustered index, data on disk is roughly sorted (clustered) with respect to an index. This benefits accesses using that index, but may hurt performance for other indices.

- Clustering can only be done with Alt. 2 or 3 B+ trees. We’ll often talk about a “Alt. 2 unclustered B+ tree” or something similar.

- Clustered indexes are more expensive to maintain (since we need to periodically update the order of files and reorganize).

- Clustered indexes also work best when heap files have extra unfilled space to accommodate inserts, resulting in a larger number of pages.

I/O Rule for Clustered Indexes

In unclustered indexes, it takes about 1 I/O per record accessed from the B+ tree, since each record is assumed to be in a different page. In clustered indexes, it takes about 1 I/O per page of records, since neighboring records are assumed to be on the same page.

Optimizations and Improvements #

Bulk Loading #

B+ Tree operations are rather inefficient in that we currently always need to start searches from the root. In addition, there is poor cache utilization due to large amounts of random access.

Bulkloading a B+ tree creates a slightly different structure, but has some nice guarantees that allow it to be used when constructing new trees from scratch.

In bulk loading:

- Sort the data by a key.

- Fill leaf pages up to size (the fill factor).

- If the leaf page overflows, then use the insertion split algorithm from a normal B+ tree.

- Adjust pointers to reflect new nodes if needed.

Sibling Pointers #

To aid in tree traversal, we can add previous and next pointers between the child nodes. When stored in sequential order, data nodes can be visited from other data nodes more quickly.

Practice Problems #

A height tree would just have a single leaf node. We know that the leaf node can hold up to entries, so this gives us a good starting point.

Now, a height tree would have one root node pointing to leaf nodes (due to the fan-out property). Since each leaf node can still hold entries, in total therer should be entries.

We can see that this pattern continues- for every additional layer, we add inner nodes, which each point to lower nodes. So we need to keep multiplying the result by , yielding the formula above.

Suppose we have a Alternative 2 clustered index built on members with a height of 5.

How many I/Os on average would it take to run the query SELECT * FROM clubs WHERE members > 60? Assume the following:

- 20 leaf pages satisfy this predicate.

- 100 records satisfy this predicate.

- .

- Each leaf page has pointers to the previous and next leaf pages.

- Each data page fits 25 records.

26 I/Os.

First, we need to find the leaf node corresponding to members = 60. It will take I/Os to find the leaf page, since the height is 2.

Once we find the first leaf page, we can continue reading the sibling pointers until we reach the end, so no further inner nodes need to be accessed. In total, we will incur I/Os reading leaf pages.

Since the index is clustered, we can assume that on average, each page of records incurs 1 I/O. There are 100 records that satisfy the predicate, and each page fits 25 records, so it takes I/Os to read the data.

In total, I/Os.

122 I/Os.

It will take the same number of I/Os to read the inner and leaf pages: 2 and 20 respectively.

However, we now need to incur an average of 1 I/O per record, rather than per page of records, so it will take about 100 I/Os to read all of the records.

In total, I/Os.