Sorting and Hashing

Introduction #

When dealing with disk operations, traditional sorting algorithms tend to create lots of random accesses and can be quite slow. We’ll explore a few strategies for creating optimized algorithms for sorting databases that work around our limited memory and buffer management abilities.

Relevant Materials #

Single-Pass Streaming #

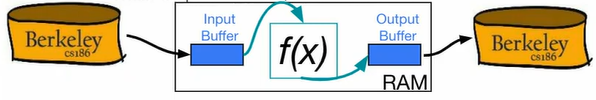

Single-pass streaming is an approach for mapping inputs to their desired outputs while minimizing memory and disk usage. We will see this principle being used for many algorithms in this course.

Main idea: There are two buffers (input and output). Continuously read from the input buffer and convert them into outputs to place in the output buffer. Only write to disk when the output buffer fills.

Optimization: double buffering

- The main thread runs the function that converts inputs into outputs.

- A second I/O thread runs simultaneously to handle the filling and draining of input and output buffers.

- If the main thread is ready for a new buffer to compute, swap buffers between the two threads.

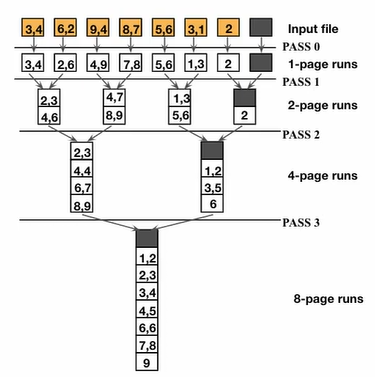

Two-Way External Merge Sort #

Two-Way External Merge Sort is a building block to generalized merge sort.

Main idea: As input buffers are streaming in, sort each input buffer, then merge two input buffers together into one output buffer using merge sort. Repeat until all pages are merged.

For larger input sets that span multiple pages, several passes are required. In each pass, pages are merged together and double in size.

I/O Cost Analysis

- Suppose we have pages.

- In every pass, we read and write each page in file, causing IO’s.

- The number of passes is logarithmic in nature:

- Multiplying the number of passes by the cost per pass gives a total cost of .

General External Merge Sort #

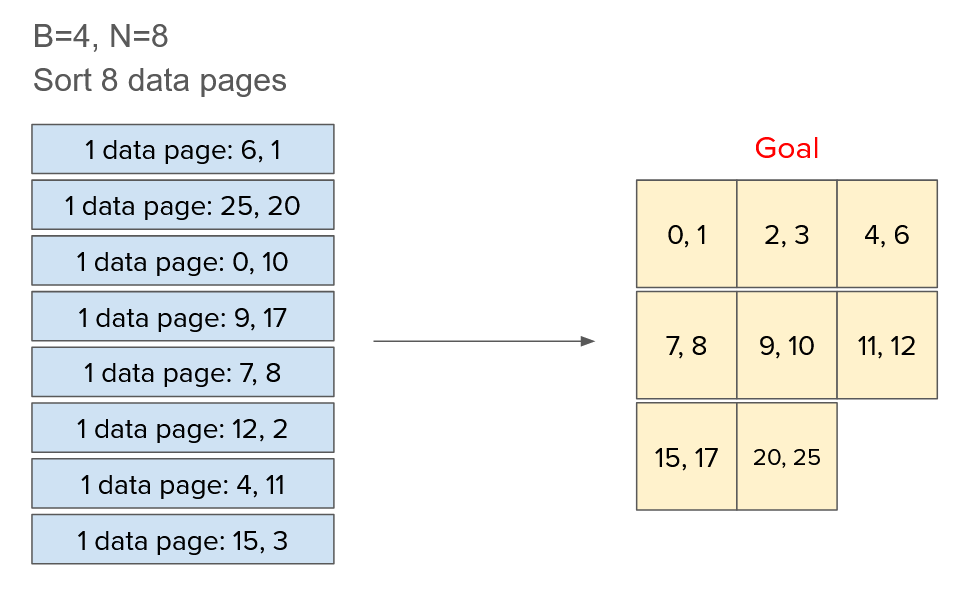

In a typical system, we have more than 3 buffer pages available to us at a time. So, we can merge more than two pages at a time. Let’s walk through how this might look like (with the example from Discussion 4):

Pass 0 #

In the example above, we have 8 data pages of 2 records each. Since we can only fit 4 pages in the buffer at once, we will need multiple passes.

For pass 0, the goal is to create the largest sorted runs possible by filling the buffer with records. Since our buffer can fit 4 pages at once, we’ll end up creating 2 sorted runs of 4 pages each. Pass 0 does not need to use an output buffer, since we’re not streaming anything! Every set of 4 pages is self-contained.

Eventually, we’ll create the two runs below by grouping 4 pages together and sorting them in memory:

[0, 1, 6, 9, 10, 17, 20, 25] (pages 0-3)

[2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, 12, 15] (pages 4-7)

This process takes I/Os, where is the total number of pages, because we need to first read all the pages then write them all back out once they’re sorted into runs.

Pass 1 #

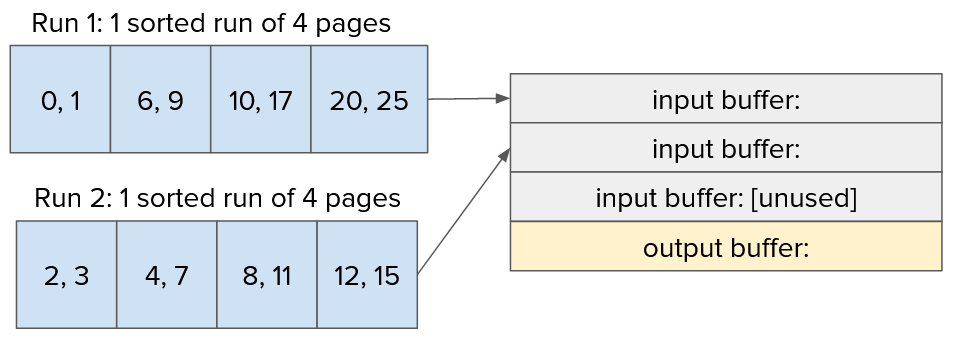

For the next pass, we do need an output buffer, since we must persist data in between runs to combine them. This is what it might look like in memory:

Now that we’re using general external merge sort, you can see that we can merge up to 3 sorted runs at the same time (). But since only 2 were created, the final input buffer will be left empty.

Now that we’re using general external merge sort, you can see that we can merge up to 3 sorted runs at the same time (). But since only 2 were created, the final input buffer will be left empty.

The process of sorting in-memory is as follows:

- Read in all of the input pages.

- Find the minimum value out of all of the input pages.

- Write that value to the output buffer, and delete it from its source input buffer.

- If the output buffer is full, write it to disk and empty it.

- If all input buffers are full, flush the rest of the output buffer to disk and we’re done!

Calculating the Number of Passes #

The number of passes required to sort pages when we have buffers is given by the equation below: The at the front is for Pass 0. This creates runs of length .

Then, in every pass, we combine runs into a single run. The algorithm completes when the number of runs left is , so we need to figure out how many times to divide the initial number of runs by before it becomes , which can be done using the term.

One implication of this equation is that the number of required passes decreases exponentially with respect to the number of buffer pages!

Calculating the I/O Cost of External Sort #

The I/O cost calculation is actually pretty simple once we know the number of passes. In each pass, we read every page in and write every page out once, so we can just multiply the number of passes by :

External Hashing #

Hashing is best for when we don’t care about the absolute order of elements, but only to group similar elements together. This is useful for GROUP BY operations.

In 61B, we learned how to create hash tables using an array of linked lists. However, this method only works if we have enough memory to store the entire collection of data at the same time, so we’ll need to modify this a bit!

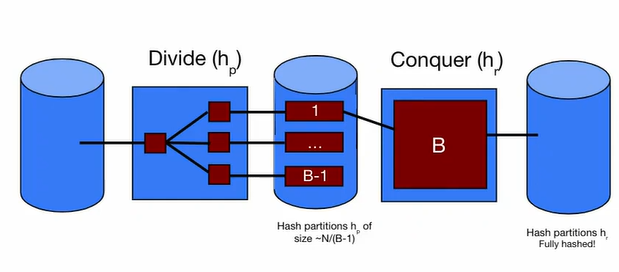

Divide and Conquer #

The main idea of external hashing is use a two-step process:

- Break down the problem into smaller parts until each subpart can fit entirely into memory.

- Combine the partitions back together to create one big hash table.

Essentially, by partitioning the values, we are splitting a large file into many smaller files, each one with at most pages.

Since these smaller files can each fit into the buffer, we can then use our normal methods to create an in-memory hash table, which will group everything together.

How is this different from sorting? #

There are a few important differences:

- Rather than creating a smaller number of longer runs for each pass, we’re creating a larger number of smaller runs.

- In the real world, no hash function can always uniformly partition data. So, we will probably end up having some groups being larger than others.

- We might end up only filling a part of a page in some partitions, even though we started with completely full pages. This means that the number of writes per pass might be greater than the number of reads. (Example: If we had and created uniform partitions, each partition would be pages long (3.5 rounded up). So we’d have 35 reads, and 40 writes.)

Use unique hash functions! #

If we used the same hash function to create partitions in every pass, then our partitions would never get smaller! So, for every pass of external hashing, we must use a different hash function.

Another related issue is when we have a very large number of identical values, since they won’t ever be broken down. When implementing hashing, we should add in a check for this case and stop recursively partitioning if it occurs.

Calculating I/O Cost of Hashing #

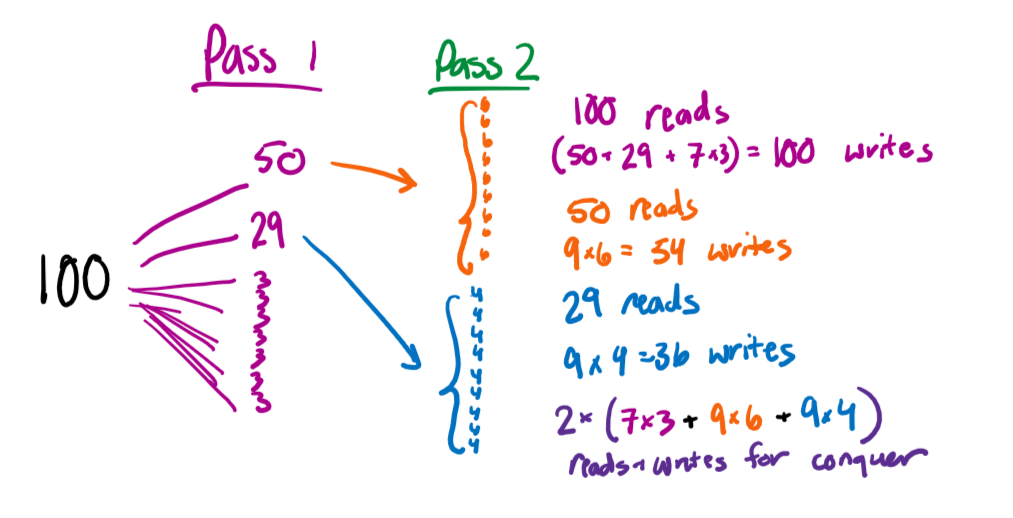

As a consequence of the above, we can’t write a clean formula for calculating the I/O cost of hashing. Luckily, there is a straightforward process we can use instead.

For this part, let’s suppose that and we have pages to hash. Our first hash function creates one partition of size , one partition of size , and seven partitions of size . All future hash functions are uniform (i.e. they create partitions of equal size).

Pass 1 #

First, let’s calculate the I/O cost of the first pass:

- We read in all pages, which takes I/Os.

- We write pages, which takes I/Os

- In total, Pass 1 takes I/Os.

Pass 2 #

For the next pass, we only advance the partitions which don’t fit in memory (). In this case, only the two large partitions (50 and 20) satisfy this, so they are recursively partitioned.

- It takes I/Os to read in the data for this pass.

- The partition of size gets broken down into equal partitions of size . This incurs I/Os to write the grouped partition back to disk.

- The partition of size gets broken down into equal partitions of size . This incurs I/S to write.

- In total, this pass incurs I/Os.

Conquer #

Now, all of our partitions fit into disk so we can run the conquer phase to group them back together! To do so, we need to read in every partition we have into memory, and write the grouped version back.

To regroup, this is what our recursively partitioned data looks like right now:

- partitions of size , from the first pass

- partitions of size , from recursively partitioning the page partition

- partitions of size , from recursively partitioning the page partition

So, to read and write all of this will take $2 \times (82 + 96 + 9*4) = 212$ I/Os

Total #

The I/O cost of hashing in this example is I/Os.