Countability

How big is infinity? Are some infinities bigger than others? The is a rather mind-boggling concept; the principles of countability will hopefully make some sense out of it.

Bijections #

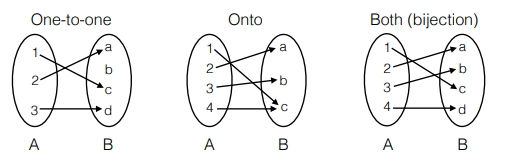

A bijection is a mapping between two sets such that there exists a unique pairing from a particular element of one set to another.

These ideas of existence and uniqueness can be formalized by considering some different types of maps:

An injection, otherwise known as a one-to-one mapping, is where each element in a set maps to a unique element in another set. (This does not, however, guarantee that the same is true the other way around- some elements in the second set may not have any mapping to them!) More formally:

A surjection, otherwise known as an onto mapping, is where there exists an input corresponding to every output. More formally:

For an injection, : there must be at least one input per output.

For a surjection, : there must be at least one output per input.

A bijection, also known as an isomorphism, is a mapping that is both one-to-one AND onto. This guarantees that the two sets must be the same size, a statement known as the isomorphism principle

Countability #

A set is countable if there is a bijection from S to the set of natural numbers or a subset of N. In other words, and have the same cardinality.

This should make intuitive sense because the natural numbers are, by definition, countable (we can start from 1, then 2, then 3… and hit them all), so if we can somehow number off some elements in a group and count them that way, then those elements are countable!

Proving that something is countable: #

- Find a bijection from S to N or N to S (must prove one to one and onto). Note that a bijection in either direction is individually valid.

- Find an injection from S to N, AND an injection from N to S.

- Enumeration: list all elements of S.

Enumerability #

Let’s now think about some ways we can list every element in a set.

Some properties to keep in mind:

- Listing a set implies that it is countable.

- Every element must have a unique, finite position on the list. (You can number them off.)

- Any infinite set that can be listed is as large as the set of natural numbers.

One method of enumerating is to find a recursive definition of the set: that is, given any one element in the set, we can define the element that immediately follows it.

One example of an enumerable set is the set of all binary strings . This is enumerable because we can say that a string with bits will be guaranteed to appear before position .

One example of a non-enumerable set is the set of all rational numbers: we can’t write fractions in an order such that you can get to the next fraction in a finite number of steps. However, the are countably infinite (read on to find out why!)

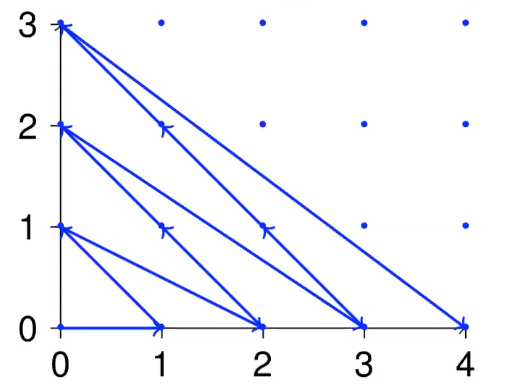

Pairs of Natural Numbers #

A pair of natural numbers has size so it is countably infinite. We can enumerate this: which guarantees that the pair is in the first elements in the list. (triangle)

Rational Numbers #

Rationals are countably infinite by writing them all in the form for a rational number . We determined that all pairs of natural numbers is countable so rational numbers are as well.

Cantor’s Diagonalization Argument #

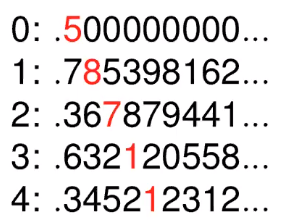

Proof by contradiction: assume that a set S is countable (even if it isn’t). Then, there must exist a listing that contains all elements in the list (enumeration).

We can construct an item that isn’t in the set by taking the diagonals of digits in the set:

This can be used to prove that real numbers are not countable.

Formal steps :

- Assume that a set S can be enumerated.

- Consider an arbitrary list of all the elements of S.

- Use the diagonal from the list to construct a new element t.

- Show that t is not in the list, but that t is in S.

- This is a contradiction.

Here’s a demonstration of the diagonalization argument in action:

Continuum hypothesis: there is no set with cardinality between the naturals and the reals.

Generalized continuum hypothesis: there is no infinite set whose cardinality is between the cardinality of an infinite set and its power set. (In other words, the power set of the natural numbers is not countable.)